You’ve heard that switching from a car with an internal combustion engine (ICE) to an electric vehicle (EV) reduces climate-warming emissions. But the extent of their positive impact is still understated, especially in Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

We at Green Energy Consumers Alliance are confident that even experts are underestimating the carbon-reduction benefits caused by an accelerating renewable energy market transformation in cities and towns throughout Massachusetts and soon, Rhode Island. Here’s why electric cars are even more effective at reducing emissions than what you’ve heard before.

Thanks to Laura Vautrinot of Mass Art for her artwork above.

EV Emissions 101

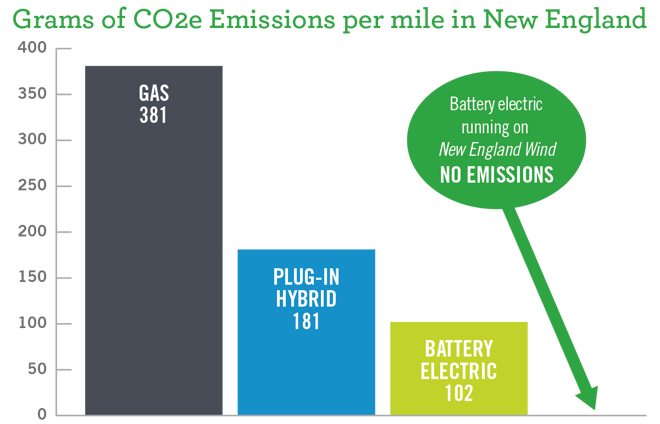

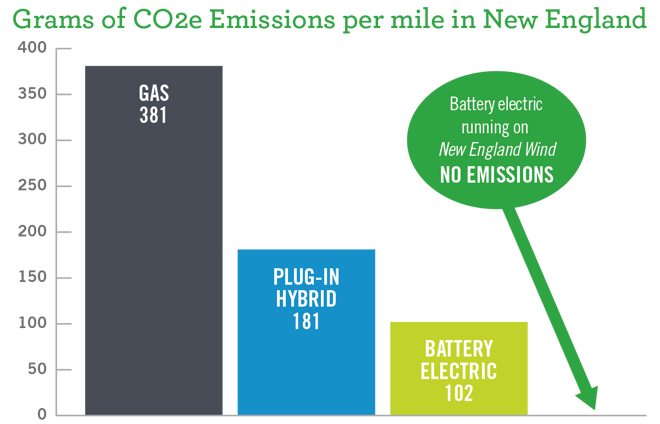

We often hear people say, “Running a car on electricity from coal-fired and oil-fired power plants can’t be cleaner than burning gasoline.” But according to the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS), the average electric car in New England emits 102 grams of CO2 per mile, 73% less than the average ICE car.* Why is that?

In terms of physics, electric cars are more efficient than the gas-powered cars they’re replacing. Combustion engines waste a lot of energy through heat output and have hundreds of moving parts, like fuel pumps, that use the gasoline’s energy but don’t contribute directly to the car’s motion. You can see a breakdown of where all that lost energy goes here.

As a result, gas-powered cars convert only about 17% - 21% of the available energy in gasoline to miles driven, compared to 77% for electric cars. EV efficiency is four times better than the average gas-powered vehicle. By driving an electric car, you’re not only reducing demand for oil, but you’re consuming less overall energy to travel the same number of miles.

That all means that today you can buy or lease a car that will reduce your driving-related emissions by pretty close to what needs to be done worldwide in thirty years.

Some states are greener than others

If you use UCS’s EV emissions estimator, you’ll get 102 grams of CO2 emissions per mile by putting in any New England zip code. The result is the same whether you are from Boston, Providence, Burlington, Bangor, Hartford, or Manchester because UCS pulls electricity emissions data from a database at the Environmental Protection Agency that has an average for all of New England in 2018.

While the EPA’s data is regional, we have state-specific data on the electricity mix for residential customers on Basic Service for customers of National Grid (in both Massachusetts and Rhode Island) and Eversource. This data can help us understand which resources are responsible for emissions now, and what they will be like in 30 years as a result of state renewable energy standards. The power-generating sources for the two utility companies aren’t identical, but they are very similar.

There is still some coal and oil in the energy mix. However, these dirty and generally old fossil-fuel-burning power plants are usually only turned on during peak energy demand when other resources are maxed out on capacity. Overall:

-

- 38% of the electricity mix is from zero-emission resources such as wind, solar, hydro, and nuclear

- 41% is from fossil fuels (natural gas, coal, and oil)

- 21% is from non-fossil sources, such as biomass, that have emissions

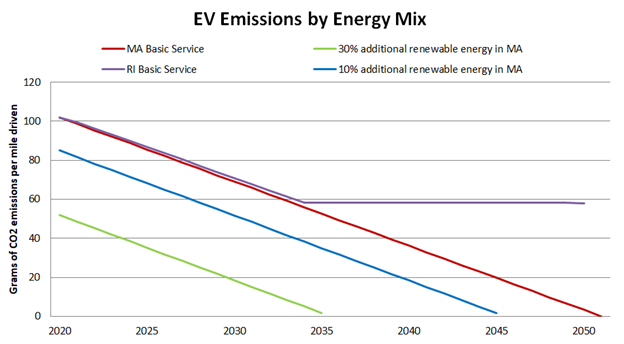

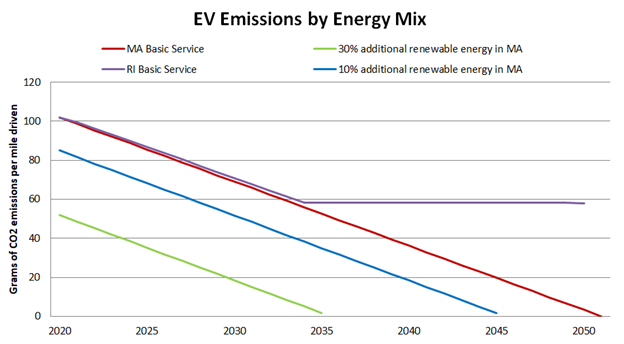

By law, customers of National Grid and Eversource are going to see the Class I renewable energy component increase by 2% per year in Massachusetts and 1.5% per year in Rhode Island. That will almost certainly increase the “zero-emissions” percentage of the electricity-generating sources at the expense of emitting resources. That 102 grams of emissions per mile figure in 2020 will therefore shrink each and every year for EVs. In some years it might shrink more than others depending upon which resources are retired.

According to law, EVs (and every other electricity-consuming appliance) in Massachusetts should become truly zero-emissions by 2050. In Rhode Island, the state law reaches a cap by 2035, so we expect to an EV’s emissions to reduce to about 58 grams per mile, which translates just 15% of today’s emissions compared to a gas-powered car. Meanwhile, we’re advocating for policy to make Rhode Island’s standard equal or better than Massachusetts.

Some cities and towns are greener than others

In Massachusetts, the model of Green Municipal Aggregation is becoming widespread and radically altering the math on emissions reductions for both power generation and vehicle electrification. With GMA, communities choose to have more renewable energy than required by law – meaning more renewable energy than National Grid or Eversource’s Basic Service. Some communities have a default product that is 5% more than Basic Service, some have 10%, and others 30% and up.

Community aggregations for electricity come in all sorts of different flavors, but the agreements that are best for consumers and the environment have a renewable energy component, shown in green here.

Let’s look at what 10% additional renewable energy does for the average EV in a Massachusetts community such as Arlington, Somerville, or Winchester, or 30% as in Brookline.

Note: the actual reduction of per-mile carbon emissions for EVs will vary slightly depending on which emitting resources are displaced by renewables. In other words, the lines will be a little squiggly instead of perfectly straight. However, this graph is a good estimate of the trends we expect to see in the long term.

By our calculations, that moves the zero-emission date for EVs in Arlington, Somerville, and Winchester moves up to 2045 and Brookline to 2035!

By 2045, emissions won’t be zero in Rhode Island, but they should be about 90% less than in 2020. But expect several communities in the Ocean State to adopt GMA soon, so watch out.

The beauty of GMA is that it provides cost savings to communities while exceeding the state’s renewable energy requirements by default. But all the GMA communities also have an “opt-up” product available so that individuals can zoom to 100% renewable energy immediately – and many people are choosing to do so. If you are not in a GMA community, no problem; you can still opt up to 100% wind power.

Not all EVs are created equal

The UCS’s estimate of 102 grams per mile may not account for GMA, but their calculator does allow you to see the results for specific EV models. Two popular (and efficient!) cars in the Drive Green program, the Chevrolet Bolt and Hyundai Kona, emit just 89 grams per mile. This pushes the Massachusetts zero-emission date up another four years to 2041, with Rhode Island getting its 90% emission reduction by then too.

At this point, we commend Tesla, which has chosen not to participate in our Drive Green program but has helped drive EV adoption across the country. The Tesla Model 3 produces just 80-86 grams per mile depending upon which variation of the Model 3 you get.

The upshot

If you don’t need a car, carry on walking, biking, or taking transit (which we’re working to electrify via our advocacy efforts, too). But if you do need to drive, for gosh sakes, get an EV. If you live in Massachusetts or Rhode Island, the emissions-reduction benefits of an EV are bigger than you probably were aware. Get an EV yesterday. If you live in a community with Green Municipal Aggregation, freedom from emissions is fast approaching.

A Chevy Bolt in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Gloucester is a GMA community, so residents save money on their utility bills while supporting the turbines in their own town.

We can do this.

Heat pumps, the equivalent to electric vehicles for space heating/cooling, show promise to reduce the emissions from buildings in a similar fashion. Stay tuned for the blog, Heat Smart with Green Power, to learn more.

*In our math, we assume that gasoline-powered cars in New England release 381 grams of CO2 per mile driven. However, it's likely that this number is conservative because producing and transporting gasoline and diesel fuels is more emissions-intensive than what most estimates assume.

Comments