Two States & Their Decarbonization challenges

Rhode Island and Massachusetts both have mandates to reduce statewide greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030...

Energy standards have changed our electricity and auto industries for the better. Now it’s time to bring the same idea to how we heat our buildings.

Energy standards have changed our electricity and auto industries for the better. Now it’s time to bring the same idea to how we heat our buildings.

Readers of our blogs know that Rhode Island and Massachusetts both have laws requiring big-time greenhouse gas emission (GHG) reductions by 2030, 45% in the Ocean State and 50% in the Bay State, respectively. A lot has been written about pathways to reducing GHG in the electricity sector. In fact, our power has been getting steadily cleaner for many years, largely because of renewable energy mandates. These mandates say that, if you’re an electricity supplier, each year you must include a higher percentage of wind, solar, and hydro in your portfolio. Both states have had such laws on the books for many years, but Massachusetts is contemplating increasing its Clean Energy Standard and Rhode Island this year took the bold step of committing to 100 percent renewable power by 2033.

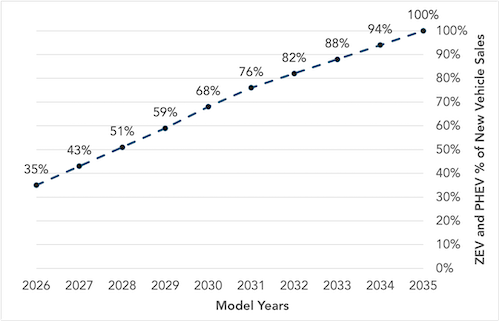

On transportation, we look west to California, which has just announced that by 2035, 100 percent of new cars purchased in the Golden State must be electric. Between now and then, EVs will make up an increasing market share each year as shown below. Massachusetts and other states are following suit. Even the carmakers supported this rule, known as Advanced Clean Cars II. It’s a standard that will transform the auto industry in a manner very similar to the renewable energy standards for electricity – gradually but certainly. What it says is that if you want to sell cars in California or Massachusetts, each year you must sell a higher percentage of vehicles without a tailpipe.

Advanced Clean Cars II Requirements Over Time (Source: CARB)

So, is it possible to formulate a policy for the buildings sector that would transform that market in a manner like we’re seeing in electricity and transportation? Yes, there is. Unsurprisingly, it’s called a “Clean Heat Standard” (CHS). According to the Massachusetts Clean Energy and Climate Plan for 2025 and 2030 (CECP), the CHS would be a major policy to drive down emissions from heating space (and water heating too). The CECP did not propose a set of rules but laid out a plausible framework. Apparently, details of a Clean Heat Standard will be revealed later this year by Governor Baker’s Clean Heat Commission.

A CHS would require a fuel supplier (of natural gas, heating oil, or propane) for heating either space or hot water to deliver clean heat solutions in increasing amounts over time. To paraphrase what the CECP says about how a Clean Heat Standard would work:

What it really boils down to is that the CHS is a new way to finance the transition from fossil fuel-based heating to zero-emission heating. Currently, most of the revenue generated for this purpose in Massachusetts and Rhode Island is from surcharges on our electricity bills. That was okay a few years ago before it became obvious that we need to electrify heating and transportation. Today, it is counterproductive to keep raising electricity surcharges because that would be a disincentive to buying a heat pump or electric vehicle. By contrast, a CHS finances clean heat through a form of carbon pricing. And that is what we need.

If you want to delve deeper into the intricacies of the CHS framework, read this document, starting on page 27. When the Clean Heat Commission report comes out, we will comment on the specifics, but for now, Green Energy Consumers has these points to make:

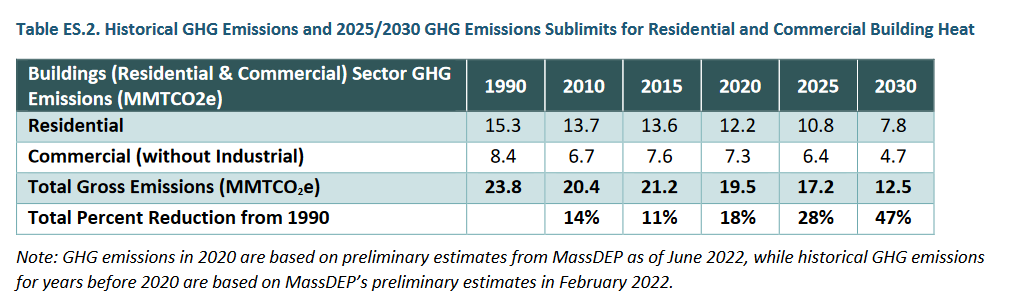

1. The amount of clean heat added through a CHS must be enough to produce GHG reductions sufficient to meet the state’s target for 2030.For Massachusetts, the economy-wide target is 50% below the 1990 baseline, with a target of 49% for the heating sector. Rhode Island does not yet have such a target for heating, but it’s obvious that it would have to be in the same ballpark. A CHS has to ramp up enough to cause emissions to ramp down. The table below shows how much building sector emissions from heating will have to drop according to the Massachusetts CECP.

To be considered a success, the CHS must be rigorous enough to cause enough clean heat to be deployed (meaning produced, purchased, measured, and verified) to displace enough fossil fuels to reach our GHG reduction targets. Look at the three columns on the right and the row with Total Gross Emissions in the table above. From 2020 to 2025, emissions will have to decrease by 2.3 million metric tons (or 12 percent). That’s roughly 2.3 percent per year. Progress of that magnitude has never been achieved. By comparison, the Mass Save Three-Year Plan for 2024-2025 projects an estimated annual GHG savings of 846,000 tons. Mass Save, which is the program administered by investor-owned utilities and the Cape Light Compacts covers about 85% of the Commonwealth’s energy usage. Municipal utilities make up the remaining 15%, but their efficiency programs are weak compared to Mass Save. There are other ways to save energy and reduce GHG in the building sector, such as through building codes and appliance standards, but however you analyze the situation, it will be a tough climb to 2.3 million tons by 2025 and 7.0 million tons by 2030.

To pick out one key part of Mass Save’s plan for 2022-2024, the program will spend about $800 million to install approximately 70,000 heat pumps. To meet the Commonwealth’s target for 2030, Massachusetts will have to install about that many heat pumps or more per year. Again, this is a level of investment that should not be funded by increasing electricity rates.

To pass the acid test, the Clean Heat Standard must raise enough revenue to pay for enough GHG-reducing measures to get the job done. It has to disrupt the heating industry.

2. We must look really closely at what qualifies as “Clean Heat.”

There will be a lot of debate about what measures will qualify. The gas utilities will push for “renewable natural gas” (RNG) and hydrogen as fuels that they can blend into their pipelines with regular methane. The utilities have a desire to blend in RNG and hydrogen to extend our dependency upon their distribution infrastructure, which is how they make their profits. We oppose that approach. To the extent that organic material from livestock, agricultural waste and sewage treatment facilities, and municipal solid waste is available, it’s better economically and environmentally to run it through an anaerobic digester and then a power generator.

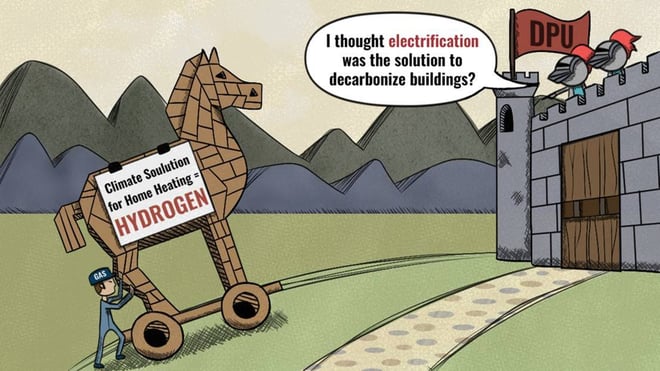

As far as hydrogen is concerned, it will have a place in our energy system, but not as something we transport through our distribution system in order to heat our buildings. Our colleague, Kyle Murray of Acadia Center, explains well why hydrogen should not play a role in heating buildings.

As far as hydrogen is concerned, it will have a place in our energy system, but not as something we transport through our distribution system in order to heat our buildings. Our colleague, Kyle Murray of Acadia Center, explains well why hydrogen should not play a role in heating buildings.

Thinking outside the pipe, heating oil dealers will want to earn credit for blending in biodiesel. On that, science should rule the day. Taking the whole lifecycle into account, which biodiesel feedstocks (I.e. soybean oil, waste vegetable oil) really reduce emissions? Scoring the emissions benefit will be an important job for the Department of Environmental Protection.

3. We also must take steps that will ensure social equity in the CHS.

For example, we could ensure that a significant portion of clean heat credits goes towards helping certain types of buildings that are important to society go green, such as affordable housing, schools, other public buildings, and health care facilities. Low-income folks with high gas or oil consumption ought to be at the head of the line for clean heat. And we need to watch out for the impact a CHS program would have on those consumers who remain on gas, oil, and propane.

For example, we could ensure that a significant portion of clean heat credits goes towards helping certain types of buildings that are important to society go green, such as affordable housing, schools, other public buildings, and health care facilities. Low-income folks with high gas or oil consumption ought to be at the head of the line for clean heat. And we need to watch out for the impact a CHS program would have on those consumers who remain on gas, oil, and propane.

On the supply side, to make all these clean heat credits, we are going to have to transform the heat pump market. That means finding ways to drive down the cost and improve the quality of installations. This will require a huge, multi-year commitment to workforce development. In 2022, we can already see that demand for heat pumps is exceeding supply, largely because contractors do not have enough trained personnel. So there has to be a workforce development policy that is commensurate with the goals of the CHS.

We know that no one likes the word bureaucracy. But it will be the job of state agencies to determine which measures earn credits, how many credits we need each year overall, and how to measure and certify individual projects that apply for credit.

6. Utilities will have to adapt to the CHS and not the other way around

The purpose of a Clean Heat Standard is to efficiently organize markets towards the societal goal of equitably reducing greenhouse gas emissions. The natural conditions that give utilities monopoly status over the distribution of gas and electricity do not apply to the tasks of installing heat pumps and insulation. The opportunity to profit from products and services that stem from the CHS should be open to all companies that can demonstrate competency.

So now we wait to see what the Clean Heat Commission report says about the Clean Heat Standard. In Massachusetts and Rhode Island, we have to decarbonize every existing building for environmental and public health reasons. In our view, the CHS will be essential. And in doing so, we will realize economic benefits as we slash our imports of gas and oil from all over. But it won’t be easy. We can win on this with a good policy design and an “all of society” approach with the government, consumers, nonprofits, and private businesses – all working towards a common goal.

Rhode Island and Massachusetts both have mandates to reduce statewide greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2030...

In Massachusetts, both the legislative and executive branches are considering a Clean Heat Standard (CHS) to...

Comments