In the course of our work promoting the electrification of transportation and heating, we are often asked how the grid is going to hold up with the increased demand caused by heat pumps and electric vehicles (EVs). Recently, one of our favorite state legislators said he gets that question frequently too. So, here’s our response.

In the course of our work promoting the electrification of transportation and heating, we are often asked how the grid is going to hold up with the increased demand caused by heat pumps and electric vehicles (EVs). Recently, one of our favorite state legislators said he gets that question frequently too. So, here’s our response.

First: Change Is Gradual

While we would like to see faster adoption, heat pumps and EVs are going to replace their fossil fuel alternatives gradually over time. Using ballpark figures, Massachusetts hopes to have about a million heat pumps and EVs each by 2030. That may sound like a lot, but we have 2.7 million homes and 5.5 million cars in the Bay State. Rhode Island’s climate plan is similar, but a bit less ambitious and scaled to the Ocean State.

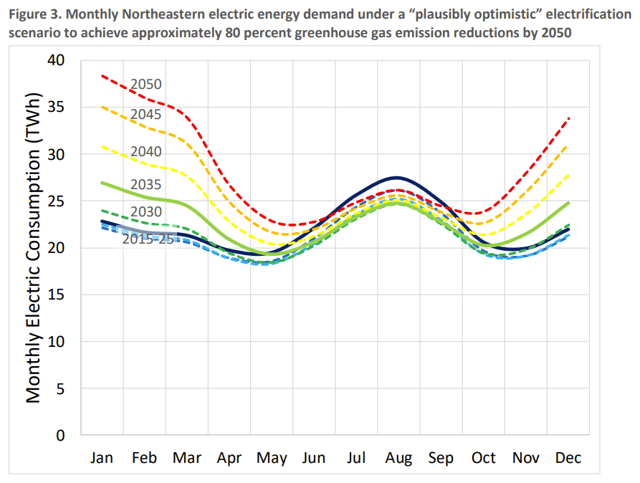

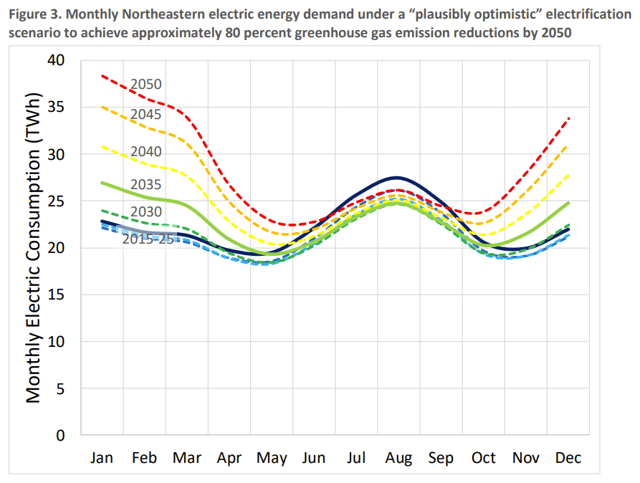

Heat pump and EV adoption will ramp up this decade, but it’s not going to stop in 2030; this transition will keep going. As more and more people adopt heat pumps and EVs, electricity use will increase. Our favorite illustration of how this might play out is this graph produced by Synapse Energy Economics in 2017. It shows that energy consumption will increase in all twelve months of the year over the years, but that the growth will be most pronounced during the winter.

Source: Hopkins et al., 2017. "Northeastern Regional Assessment of Strategic Electrification." Synapse Energy Economics and Meister Consultants Group for Northeast Energy Efficiency Partnerships.

Source: Hopkins et al., 2017. "Northeastern Regional Assessment of Strategic Electrification." Synapse Energy Economics and Meister Consultants Group for Northeast Energy Efficiency Partnerships.

This gradual increase in adoption means that we have time to plan. By “time to plan,” we do not mean “sit back and wait to deal with this until later.” We mean plan and build the grid we need.

Second: Increased Electrification Means More Revenue for Upgrades

Often, part of the “how are we going to do this?” question is really “how are we going to pay for this?” The good news is: the owners of all these heat pumps and EVs will have to pay for the electricity they use. And what they pay will finance the transmission lines, substations, transformers, and the generation we need to meet the increased load.

There is already promising data from places that are further along the adoption curve on these key technologies. In California, for example, where EV adoption is much higher than in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, the money paid into the system by EVs between 2012 and 2021 outstripped the costs of service upgrades to charge those EVs by $1.4 billion. This means that increased EV adoption brought down per-kilowatt-hour costs for all ratepayers (see: NRDC).

There is already promising data from places that are further along the adoption curve on these key technologies. In California, for example, where EV adoption is much higher than in Massachusetts and Rhode Island, the money paid into the system by EVs between 2012 and 2021 outstripped the costs of service upgrades to charge those EVs by $1.4 billion. This means that increased EV adoption brought down per-kilowatt-hour costs for all ratepayers (see: NRDC).

If you’re worried about the owners of these cleaner technologies bearing the cost burden, remember that what the owners will pay for that electricity will be offset by paying less for fossil fuels – the fracked methane, heating oil, propane, gasoline, and diesel they would have otherwise purchased. That’s a win for everyone.

Third: We have tools to manage this transition

Our electric infrastructure is built out to make sure that at moments of peak demand (when everybody turns on their washing machines and their microwaves and their TVs), power still flows from generators to end users. But most of the time, demand is well below that peak and that infrastructure is effectively overbuilt. As demand starts to increase thanks to electrification, it will be much cheaper (not to mention environmentally and socially more responsible) to make better use of our existing infrastructure rather than overbuilding more. What does this look like? It looks like investing in energy storage that will allow us to put power into the grid when the grid needs it, the smart meters that will allow us to respond in real-time to changing conditions on the grid, and grid modernization that will help us upgrade and conserve all across the board.

The most powerful tool we have in the toolbox is the fact that we can shift electricity use from peak moments to off-peak moments. Of course, there are some uses for electricity that we can’t shift to off-peak times. We need lights when it’s dark. The fridge needs to run to keep the food cold. We want AC when it’s hot (by the way, heat pumps also provide cooling far more efficiently than room ACs). But cars sit around unused for 20 or more hours per day. An EV is the easiest electric appliance to manage. We can charge it when we’re sleeping and on weekends – times when the grid is “off-peak” and therefore unstressed. Using that spare grid capacity during those times is efficient and helps reduce costs for everyone.

The most powerful tool we have in the toolbox is the fact that we can shift electricity use from peak moments to off-peak moments. Of course, there are some uses for electricity that we can’t shift to off-peak times. We need lights when it’s dark. The fridge needs to run to keep the food cold. We want AC when it’s hot (by the way, heat pumps also provide cooling far more efficiently than room ACs). But cars sit around unused for 20 or more hours per day. An EV is the easiest electric appliance to manage. We can charge it when we’re sleeping and on weekends – times when the grid is “off-peak” and therefore unstressed. Using that spare grid capacity during those times is efficient and helps reduce costs for everyone.

EVs are increasingly becoming equipped with “bi-directional charging,” which allows a car to feed power from its battery into a building, just like a stationary battery. Multiply a few million EVs in New England times batteries with 60 or more kilowatt hours of capacity and you’ve got a great resource for meeting demand during peak hours.

Of course, how fast and high energy use goes up will also depend upon a lot of things: how well buildings are insulated, how efficient the heat pumps are, and whether we can all learn to time our dishwashing and clothes washing too.

The Real Question: How Can We *Not*?

When people ask “how can we manage this?,” we want to ask “how can we not?” It’s a scientific fact that our consumption of fossil fuels causes health problems – sickness and morbidity. How will society pay for that? The answer is, unfortunately: we will do what we have always done – not internalizing those costs into the price of fossil fuels, but foisting those costs onto health insurance and the government and accepting as immutable the human suffering they cause.

Health issues aside, our consumption of fossil fuels is causing all kinds of economic, social, and political damage from hurricanes, rising sea levels, desertification, lower worker productivity due to an increasing number of heat waves – and so much more. Who will pay for all that? The answer is the same. We will.

So, for those who are nervous about the future of our grid as we make it greener and more dynamic, we say: We can do this. We just need to plan ahead for a change. What we cannot do is slow down the transition to clean energy.

There is already promising data from places that are further along the adoption curve on these key technologies. In California, for example, where EV adoption is

There is already promising data from places that are further along the adoption curve on these key technologies. In California, for example, where EV adoption is  The most powerful tool we have in the toolbox is the fact that we can shift electricity use from peak moments to off-peak moments. Of course, there are some uses for electricity that we can’t shift to off-peak times. We need lights when it’s dark. The fridge needs to run to keep the food cold. We want AC when it’s hot (by the way, heat pumps also provide cooling far more efficiently than room ACs). But cars sit around unused for 20 or more hours per day. An EV is the easiest electric appliance to manage. We can charge it when we’re sleeping and on weekends – times when the grid is “off-peak” and therefore unstressed. Using that spare grid capacity during those times is efficient and helps reduce costs for everyone.

The most powerful tool we have in the toolbox is the fact that we can shift electricity use from peak moments to off-peak moments. Of course, there are some uses for electricity that we can’t shift to off-peak times. We need lights when it’s dark. The fridge needs to run to keep the food cold. We want AC when it’s hot (by the way, heat pumps also provide cooling far more efficiently than room ACs). But cars sit around unused for 20 or more hours per day. An EV is the easiest electric appliance to manage. We can charge it when we’re sleeping and on weekends – times when the grid is “off-peak” and therefore unstressed. Using that spare grid capacity during those times is efficient and helps reduce costs for everyone.

Comments