It’s imperative that we all switch from internal combustion engines to electric cars for several compelling reasons. The most important is that reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions enough to save the planet depends upon it. But what’s particularly exciting is: we can magnify the benefits of EVs by managing when we charge them.

Warning: There’s a lot of math in this blog, but it’s easy!

The status quo

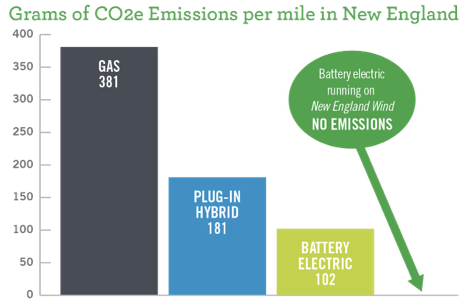

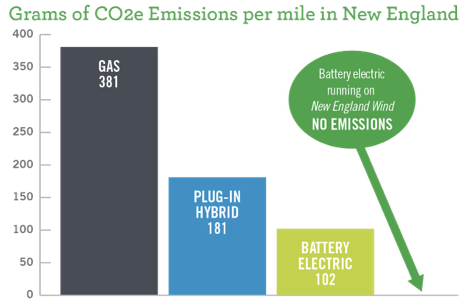

No matter when you charge your electric car, it's a good thing. Right now, an EV in New England causes emissions that are just one fourth of what you get from petroleum. And the emissions are going down each year thanks to state renewable energy mandates.

EV drivers in Massachusetts communities that have adopted Green Municipal Aggregation (GMA) already produce fewer emissions than EVs charged in towns without GMA. And of course, there are lots of other personal and social benefits from driving electric vehicles. So from a policy perspective, the primary goal should be increasing overall adoption of electric vehicles.

A important secondary goal, however, should be to encourage charging at the right times. That’s what we mean by “smart charging.”

When we charge matters

We consumers currently pay a flat retail fee per kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity that is already cheaper per mile than driving on gasoline. However, the actual cost to the grid of bringing power to you to charge your car (or your phone, for that matter) varies over time. Costs are high when demand is high: for example, in the winter when lights are on at home and work, or in the summer when ACs are blasting. Conversely, costs are low when demand is low: for example, at 2 am when we’re all asleep on a cool evening. Demand is almost always low on the weekends.

Consequently, we can add to the stack of benefits by charging our EVs at the right times, i.e. when electricity is cheapest and cleanest. Luckily, we can do this “managed charging” because EVs are not your typical home appliance. We could turn our lights on and run the vacuum at 3 am, but that would be silly. EVs represent a prime example of an electricity end use that we can easily schedule; they’re parked the vast majority of the time and power prices are almost always very low when you are asleep!

Electric utilities want to make sure that EV owners don’t charge when demand and costs are already high (“peaks”), but instead direct charging to occur when demand and costs are low (“off-peak”). Many utilities across the country try to encourage “smart” charging behavior like this by offering discounted rates for off-peak charging. And as with many issues involving utility regulation and rate structures, change is coming. But too slowly for our taste.

What are our utilities doing so far?

In Rhode Island, National Grid has been approved to run a pilot program to study charging behavior called Smart Charge RI Rewards. We think it's a step in the right direction and we encourage any EV owner from the Ocean State to participate. As an organization, we hope that National Grid and the Public Utilities Commission learn from the pilot and scale up the program before long.

As part of Mass Save, Eversource has a program called the EV Home Charger Demand Response Program, in which customers are encouraged to charge less during periods of peak demand.

In Massachusetts, National Grid is seeking approval to roll out an off-peak charging pilot program. National Grid has suggested reducing rates for off-peak EV charging by six cents per kWh in summer and four cents per kWh in winter – overall, call it a nickel. They base those numbers on the difference between wholesale electricity rates (what generators charge suppliers) during peak periods versus off-peak periods for those times of year.

This raises a question. Is a nickel per kWh the right value? Let’s look at what some experts are saying.

Synapse Energy Economics analyzed how EVs are affecting two big utilities in California, where EV adoption is far ahead of any other state. What they found, from a macro perspective, is that EV drivers pay utilities more money than it takes to provide the EVs with electricity. As a result, EV adoption has been pushing electric rates down for non-drivers. (Another good read with similar information is “A Comprehensive Guide to Electric Vehicle Managed Charging.”)

After reading the Synapse report and National Grid’s pilot proposals for off-peak charging in Massachusetts, in March 2019, we asked Allied Economics Clinic (AEC) to do a micro analysis. According to AEC, National Grid calculated about the right difference between peak and off-peak wholesale energy costs (including capacity) based upon current conditions.

But conditions are changing. Lawrence Berkeley Labs modeled the difference between wholesale peak and off-peak prices into the future and found that the difference is expected to grow over time as we add wind and solar. Particularly, they found that we would see many more hours during the year with very low wholesale power prices. That's yet another good reason to find ways to find good uses for an increasing amount of cheap, clean power.

But wholesale prices are not the whole story! Charging off-peak also makes better use of the transmission and distribution system. If you look at your electricity bill, “T&D” costs are considerable. AEC estimates that National Grid in Massachusetts would avoid transmission and distribution costs by 2.6 cents for each kWh charged off-peak (and acknowledges that that calculation could be refined with more information from the utility).

So perhaps a better value to the system for off-peaking charging is 7.6 cents per kWh; 5 for wholesale energy costs + 2.6 for transmission and distribution. This would apply to the avoided costs for National Grid in Massachusetts, but the concept is the same for National Grid in Rhode Island, Eversource in Massachusetts, and other New England utilities.

Remember how one benefit of EVs is their reduction of greenhouse gas emissions? That’s a value that is monetized in official evaluations of our states’ energy efficiency programs (Mass Save in Massachusetts and EnergyWise in Rhode Island). When a utility helps you buy an LED light bulb, high-efficiency refrigerator, or insulation, they account for avoided emissions per order of state regulators. AEC reports that the recognized value for avoided CO2 emissions in Massachusetts is $41 per ton per the Global Warming Solutions Act. Rhode Island has a similar set of climate goals as Massachusetts, but without a mandate. If Rhode Island were serious about reducing GHG emissions, it would likely value each avoided ton of CO2 emissions around $41 as well.

How would we apply the avoided GHG concept to EVs? Right now, an EV is responsible for producing about 3 tons of CO2 per year less than an internal combustion engine. Using an average of 3,000 kWhs per year for the EV, this translates to a greenhouse gas benefit of 4.1 cents per kWh. (For those of you who like math: 3 tons/year * $41/ton = $123/year. $123/year ÷ 3,000 kWh/year = $0.041/kWh.) Technically, this goodie comes during most on-peak charging hours too, but we can choose how to apply it as an incentive. Why not add it to the off-peak charging discount to really encourage charging at the best times – generally nights and weekends?

Now we’re up to 11.7 cents per kWh for having an EV and charging it off-peak (5 for wholesale energy costs + 2.6 for transmission and distribution + 4.1 for GHG benefits).

It makes sense to have a smart subsidy if we want smart charging. The 7.6 cents for wholesale energy, transmission, and distribution would not be coming out of the pocket of non-EV drivers at all because they are based upon avoided costs to the system. And 4.1 cents for GHG reduction is going to be paid by all of us one way or another because that’s the cost of complying with the climate action legislation.

We could go even further

The bigger the off-peak discount, the more likely it is that the price differential will actually incentivize different charging behavior. So, it’s worth looking for other values are sensible and fair.

Right now, National Grid and Eversource customers in Massachusetts and Rhode Island pay a small fee for every kWh they consume to fund each state’s energy efficiency program (Mass Save and EnergyWise, as mentioned above). Each dollar that flows into the energy efficiency coffers results in much more than a dollar of benefits for the grid (and consumers!).

When a driver switches from a gas-powered car to an electric car, they will purchase more kWh, which means the amount they pay into these state programs for energy efficiency increases. In Massachusetts and Rhode Island, this charge is about 1 or 2 pennies per kWh. So, an EV using 3,000 kWh per year would pay about $60 into these energy efficiency programs. Why not rebate that money right back to the EV driver? After all, the mere fact that they are switching to an electric vehicle (regardless of when they charge, but particularly if they charge off-peak) is fulfilling the goals of the states’ energy efficiency program: it’s causing the more efficient use of energy and saving all consumers money. If we take those 1 or 2 cents per kWh that an EV will pay into the energy efficiency program and send them back to drivers in the form of an off-peak discount, we can self-finance a larger incentive.

Adding the efficiency charge brings the total up to about 13 cents per kWh (5 for wholesale energy costs + 2.6 for transmission and distribution + 4.1 for GHG benefits + ~1 for energy efficiency). This level of discount aligns the interests of EV drivers and non-drivers alike by capturing the social benefits of EVs and managing charging without costing those who don't own an EV. With a discount of 13 cents per kWh, if the average driver did all their charging off-peak, they’d be paying only about 8 cents per kWh, instead of the normal ~21. Over the course of a year, that driver would save about $390 per year compared to the full retail rate for electricity. And that would mean paying an electricity rate equivalent to less than a dollar for gasoline. We’re the Green Energy Consumers Alliance, so we think that's pretty cool.

You might call for taxing gasoline a lot more and we would not argue. We’re just pointing out that utility rates for EVs can and should be adjusted to account for all the good EVs create and all the bad they avoid—especially when charged off-peak.

A healthy debate

We’re not done yet; the public health benefits that come from driving without a tailpipe are huge, but not recognized or valued by utility regulators.

A 2016 American Lung Association report calculated that the health costs of gasoline is $0.74/gallon. If we generously assume that the average car gets 30 miles/gallon, the public health costs of driving a mile on gasoline are ($0.74/gallon ÷ 30 miles/gallon = $0.02/mile). An EV is about 75% cleaner than gasoline, so a health benefit of an EV is about 1.5 cents per mile, which translates to yet another nickel per kWh.

So: the public health benefits of driving electric come out to another 5 cents/kWh. If we could add those to that off-peak discount, it would increase to 18 cents/kWh.

The fact that we don’t account for these public health benefits is as much a policy failure as it is a market failure. It’s a prime example of policymakers working in siloes. Given the high cost of medical care, this is unfortunate. But as much we would love to add the value of public health improvement to the off-peak rebate, it would require a major rule change and possibly legislation.

All in all…

Utilities are on the right track by offering an off-peak charging rebate. But the proposals we have seen thus far are too modest. Let’s account for all the benefits and do what it takes to raise EV adoption to the levels we need to meet our climate goals.

While we wait for regulators and utilities to set the right price signals, if you drive an electric vehicle already, we hope you’ll charge off-peak anyway.

Many thanks to this cooperative in North Carolina for this excellent reminder.

P.S. We hope we have piqued your interest about how timing is everything in electricity. It just so happens that this Wednesday, July 17, forecasters are saying that electricity demand will reach its highest point for the year, thanks to expected heat and humidity. Those of us with electric cars should plan ahead and skip charging on Wednesday. And for all of us, EV drivers or not, we have a program called Shave the Peak that is designed to reduce the economic and environmental costs of high demand.

Update, September 3:

EV models vary by their ability to support smart charging, but in general, you can expect fully-electric cars to offer charging schedulers.

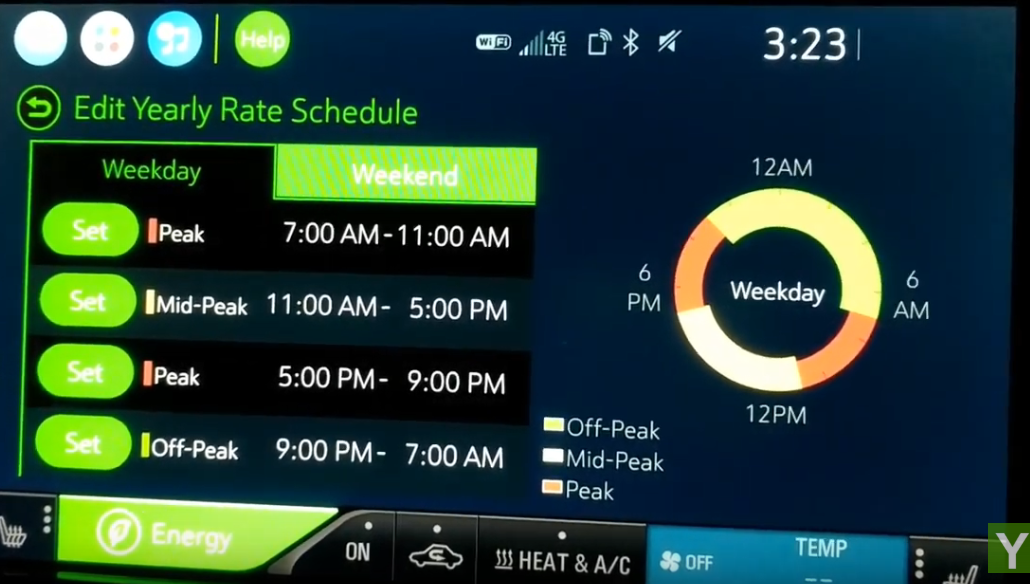

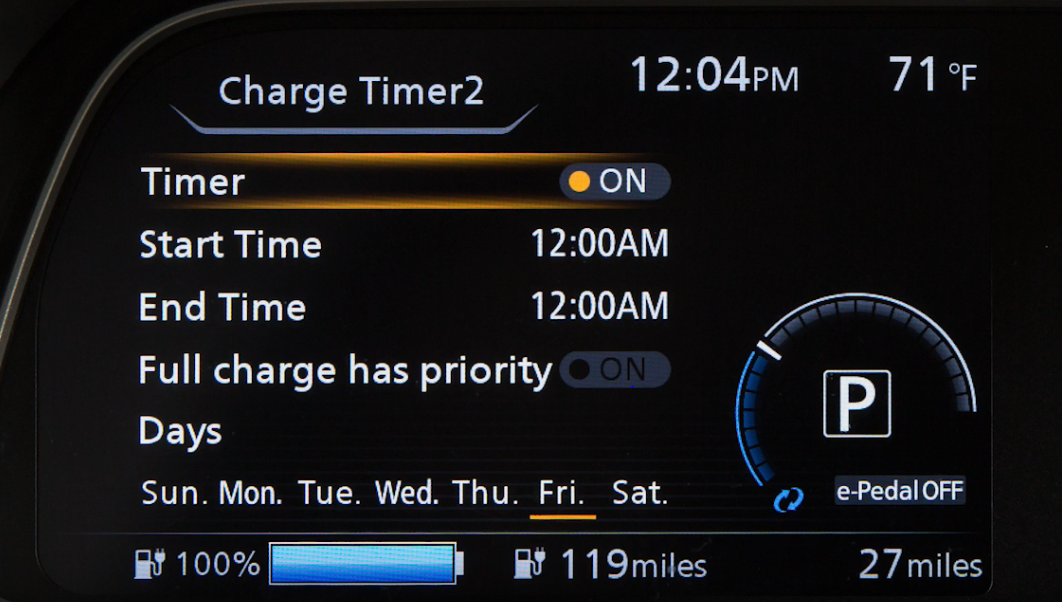

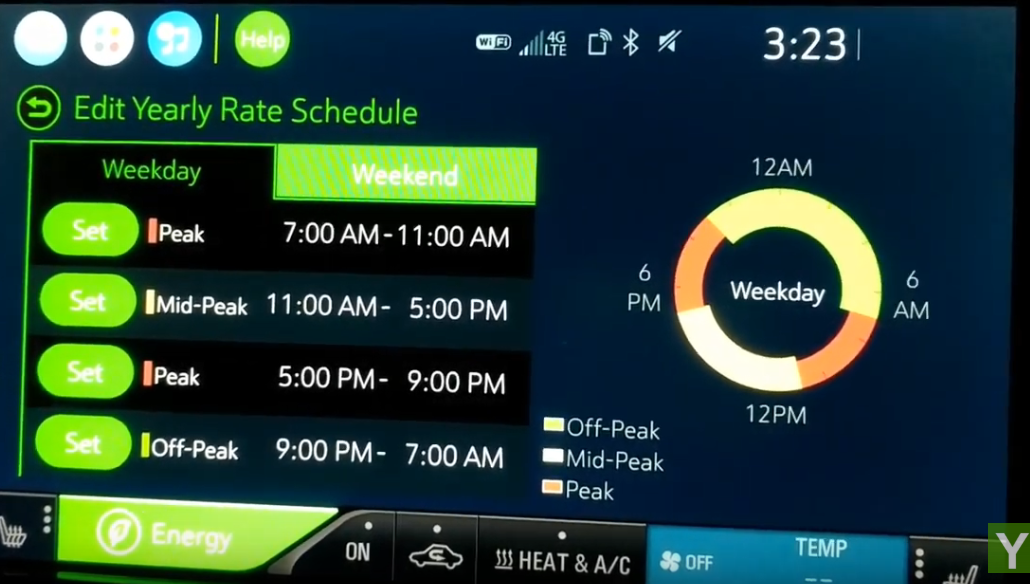

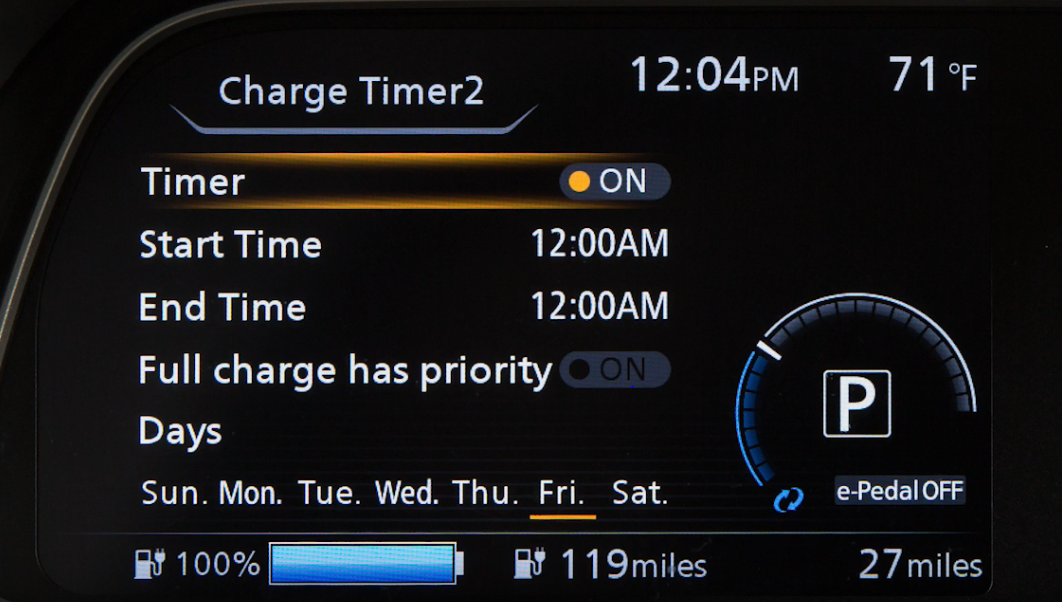

The Chevrolet Bolt, Kia Niro, Hyundai Kona, BMW i3, and Hyundai Ioniq have the most advanced smart-charging features. These models can manage charging based on peak and off-peak times that the driver selects. It is also possible to simply set a start/end time for charging these cars, which can vary depending on the day of the week. The Nissan LEAF only has the ability to set start/stop charging times, but there’s no way to differentiate between peak and off-peak rates.

Above is a dashboard photo of the smart charging settings available on the Chevy Bolt. The driver can set peak times and opt to either prioritize off-peak charging when possible or only charge off-peak.

For comparison, below is a dashboard photo of the charging scheduler for the Nissan LEAF. The driver can set start and end times for charging and have different schedules for different days of the week to match their driving habits.

Plug-in hybrids may or may not have smart-charging settings available. The Toyota Prius Prime, Mitsubishi Outlander PHEV, and Honda Clarity PHEV do not have charge-scheduling. The Subaru Crosstrek Hybrid, Kia Niro PHEV, and Chrysler Pacifica Plug-in Hybrid have a start/stop time scheduler like the LEAF.

Comments