National Grid’s Rate Increase in Rhode Island: Will it Transform the Power Sector?

Original artwork from Mass. College of Art and Design student, Erin MacEachern, created for People's Power &...

If you haven’t seen it yet, you will. Gas utilities everywhere are putting out propaganda that they can decarbonize the gas that flows through our pipes to heat our homes and businesses. National Grid, one of the major utilities in Massachusetts and New York, has produced a document with its vision of a clean energy future. If you read through the paper carefully, you will see how important it is to the gas utility to mix Renewable Energy Gas (RNG) and hydrogen with natural gas (fracked methane). Whether it’s in the public interest is a different question.

If you haven’t seen it yet, you will. Gas utilities everywhere are putting out propaganda that they can decarbonize the gas that flows through our pipes to heat our homes and businesses. National Grid, one of the major utilities in Massachusetts and New York, has produced a document with its vision of a clean energy future. If you read through the paper carefully, you will see how important it is to the gas utility to mix Renewable Energy Gas (RNG) and hydrogen with natural gas (fracked methane). Whether it’s in the public interest is a different question.

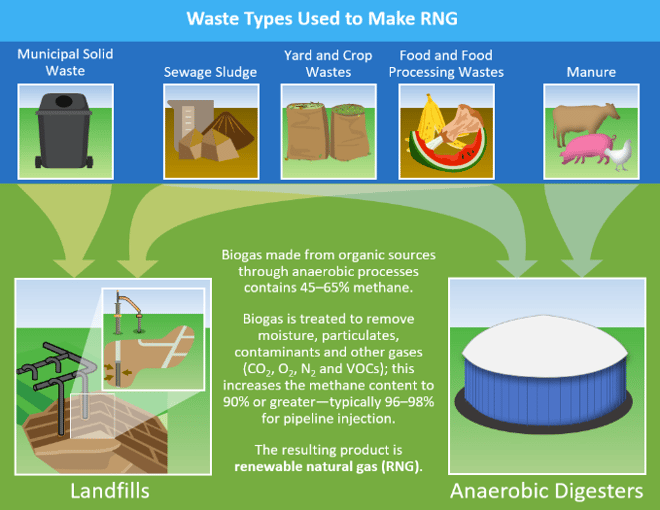

According to the federal Environmental Protection Agency renewable natural gas (RNG) is a term of art used to describe biogas that has been upgraded for use in place of fossil natural gas. The biogas used to produce RNG comes from a variety of sources, including municipal solid waste landfills, digesters at water resource recovery facilities (wastewater treatment plants), livestock farms, food production facilities, and organic waste management operations.

Source: EPA (https://www.epa.gov/lmop/renewable-natural-gas)

Source: EPA (https://www.epa.gov/lmop/renewable-natural-gas)

Many gas utilities are saying that we should capture the biogas from these feedstocks and mix RNG into the pipelines that carry natural gas (fracked methane, which is mostly the chemical compound CH4) to buildings. Their point is that from a climate perspective it’s better to burn RNG in heating systems and emit some carbon dioxide (C02) than to let the biogas evaporate into the atmosphere as methane.

The gas utilities are similarly claiming that mixing “green” hydrogen from wind and solar into the pipelines is better than relying solely on natural gas (fracked methane, CH4). Hydrogen fuel is created by using a LOT of energy to split water molecules into hydrogen and oxygen. Often, that energy is provided by fossil fuels, which kind of defeats the purpose of decarbonizing! The utilities are suggesting that if we use wind and solar to do the molecule-splitting, it could help to reduce the GHG impact of heating spaces. Putting hydrogen into the pipelines for heating buildings is a bad idea on several levels, but even the utilities acknowledge that it’s not as ready as RNG might be. To the utilities, RNG is the stepping stone (read: the gateway drug) to hydrogen, so this blog is focused on RNG.

1. There’s not enough to go around.

The first point is that there just isn't enough to bother with. All of those resources listed above – gas from cow manure, landfills, wastewater facilities, and food processing – should be captured wherever possible and anaerobically digested rather than being simply emitted into the air as methane. There is significant environmental and economic value in generating electricity from these resources. Anaerobic digesters are being built at wastewater treatment facilities, dairy farms, and all sorts of other locations to generate electricity and cut down methane emissions because electricity made from anaerobic digestion is worth inclusion in renewable portfolio standards (RPS).

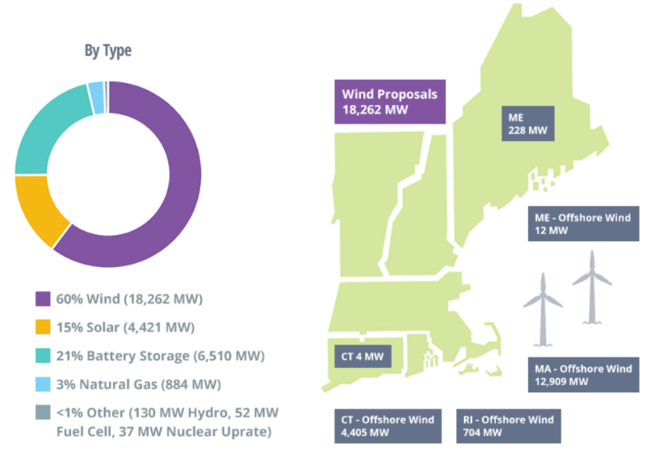

Green Energy Consumers has been following projects qualifying for the RPS for over twenty years and we have occasionally included a few anaerobic digestors in our green power portfolio. Currently, there are thirty such projects deemed eligible for the Massachusetts Class I RPS, mostly located in Massachusetts with a few in Vermont, Maine, and Rhode Island. The biggest project – by far – is the wastewater treatment facility operated by the Massachusetts Water Resources Authority on Deer Island in Winthrop, MA. Rhode Island has also qualified several fairly large landfill gas-to-electricity projects for its Renewable Energy Standard (RES). But for the most part, anaerobic digestion projects are quite small compared to what we are seeing come online from wind and solar.

The Independent System Operator of New England, which coordinates the regional electricity sector, is tracking interconnection requests from green electricity developers. According to their website, biogas applications are close to zero.

Bear in mind that New England states have had renewable portfolio standards in place for over twenty years. That has created a strong demand within the electricity market for biogas. If the supply of biogas is limited for the purpose of meeting those standards, it is simply hard to believe that there will be enough capacity to bother mixing it in with our natural gas (fracked methane) pipelines.

You can search the internet for other estimates on how much RNG is available in the United States and you won’t find much. There’s a 2013 National Renewable Energy Lab report estimating that the energy content potential from methanogenic US wastes is about 5% the size of the US natural gas system.

National Grid will claim there’s a “robust” supply of RNG supply feedstocks available for their customers in New York and Massachusetts, based upon a Request for Information they sent to potential developers. National Grid received responses totaling a potential 300 million therms of gas. Meanwhile, in Massachusetts alone, National Grid sold about 1.35 billion therms of natural gas in 2021. New York’s gas usage is obviously much greater. So, is that hypothetical supply of RNG really that robust?

2. We don’t really know what it will cost.National Grid’s press release does not identify where those projects are located or any other relevant information that anyone could use to make an assessment. How real are those potential projects? Is there a reason the developers would sell biogas to National Grid rather than sell into the electricity market? How much would it cost to bring that resource from cow to heating system, compared to any other way of keeping us warm?

3. Zero emissions means air-source heat pumps and geothermal.

Reducing building emissions 50% by 2030 and 100% by 2050 (as required in Massachusetts) will require the installation of air-source heat pumps and geothermal (whether for individual buildings or networked) powered by renewable energy. This is where our focus should be, not on ways to perpetuate the business model of investor-owned utilities.

Liberty Utilities is a much smaller gas utility in Massachusetts, serving Bellingham, Blackstone, Fall River, North Attleboro, Plainville, Somerset, Swansea, Westport, and Wrentham. In 2021, it sold about 67 million therms of natural gas, five percent of what National Grid sold in the same year. In 2022, Liberty petitioned the Massachusetts Department of Public Utilities (DPU) for the right to mix in biogas from a Fall River landfill.

In that case, the resource is clearly identified, but not the logic. Our allies at Acadia Center, Conservation Law Foundation, and Sierra Club did an excellent job as intervenors in the case, taking apart the proposal on basic economic grounds, as well as pointing out how the project would not allow Liberty to legitimately claim any greenhouse gas reduction. We were pleased to read that the Attorney General and Department of Energy Resources also oppose the project. It’s now up to the DPU to decide what Liberty Utilities may do, but from the record, it’s hard to imagine that the DPU will approve its proposal. In other words, a real-live RNG proposal fails to impress. (By the way, despite the flaw in Liberty’s petition, National Grid supported it. Birds of a feather flock together.)

Like several other states, Massachusetts and Rhode Island are contemplating the future of the gas utility and ways to decarbonize buildings. The existential question is: how do we reconcile the natural gas (fracked methane) system and the utility business model with the need to zero-out emissions by 2050? The utilities will keep pushing RNG and hydrogen as a means of maintaining a gas-based heating system, which is what their business model is based upon. Policymakers should not get distracted. Both RNG and hydrogen have a future in our energy system, but not for space heating. The smart response to clean heat is a sustained, 30-year focus on installing heat pumps and tightening up building envelopes on new and existing homes and businesses.

Original artwork from Mass. College of Art and Design student, Erin MacEachern, created for People's Power &...

Before we get into how electric cars can run on sunshine and wind power, let’s talk about old-fashioned cars...

Comments