Recently, the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released its final vehicle emissions regulations for vehicle model years 2027 through 2032. You’ve likely seen lots of headlines about this. As the New York Times put it, “in terms of lowering the emissions that are heating the planet, this regulation does more than any other climate rule issued by the federal government and more than any measure planned in the remainder of Mr. Biden’s first term." In this blog, we’ll cover what these regulations are, why they’re so important, and how they interact with electric vehicle (EV) policies in Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

First: What Standards?

Thanks to the Clean Air Act, the federal government has the authority to regulate emissions from vehicles. The standards we’re talking about today set fleet-wide average emissions standards that automakers must meet for each model year for a range of pollutants. An automaker might sell some vehicles that are more polluting than the standard and others that are less polluting, but on average, they have to meet a grams/mile pollutant standard across the fleet in any given year. (If they don’t, the automaker has to pay a fine.)

The standards released by the EPA are known as “Multi-Pollutant Emissions Standards” and are distinct from (but complementary to) the Corporate Average Fuel Efficiency (CAFE) standards that come out of the federal Department of Transportation. (We agree; it’s confusing.)

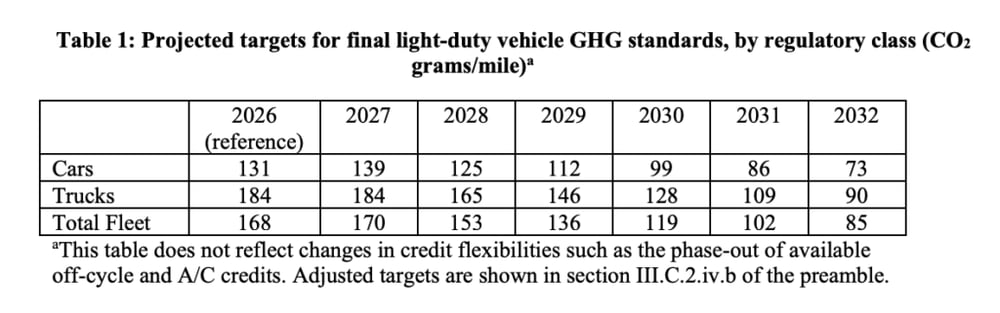

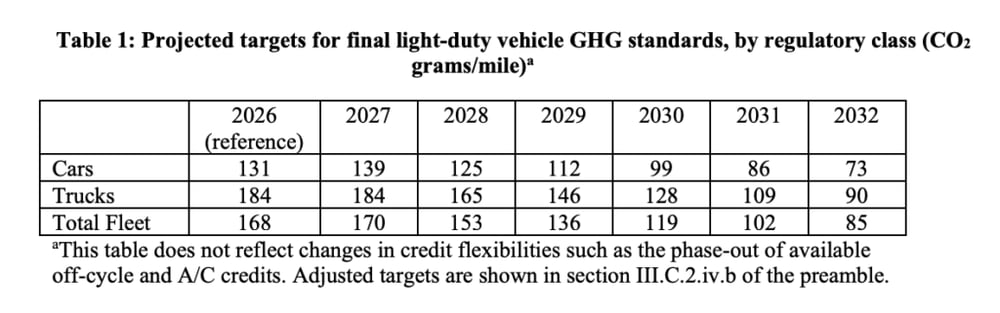

Regulations on vehicle emissions have existed since the 1970s on pollutants like particulate matter and nitrogen oxides (both of which harm human health). In 2010, the EPA added greenhouse gases as a pollutant to these Multi-Pollutant rules. The standards just released by the EPA are a continuation of existing rules and will kick in for model year 2027 through 2032. There are different standards for different vehicle classes, and it gets very complicated very quickly, but here’s what the final rule says about light-duty vehicles’ greenhouse gas emissions, in terms of grams of carbon dioxide (CO2) released per mile driven.

These regulations are a win-win-win: they reduce greenhouse gas emissions, reduce pollution that harms human health, and they save drivers across the country a huge amount of money.

EPA Standards & Electrification

These new regulations are not a ban on gas cars. The standards regulate the impact we’re trying to avoid (pollution), not the technology choice of manufacturers. For example, automakers may choose to add particulate filters on some of the gas cars they produce, or produce more plug-in hybrids vs electric vehicles. That choice is left up to the market. However, it is true that overall, these standards will lead to more electrification, because there’s only so much more emission reductions we can squeeze out of internal combustion engines before it’s simply a better choice for the consumer and the automaker to go electric.

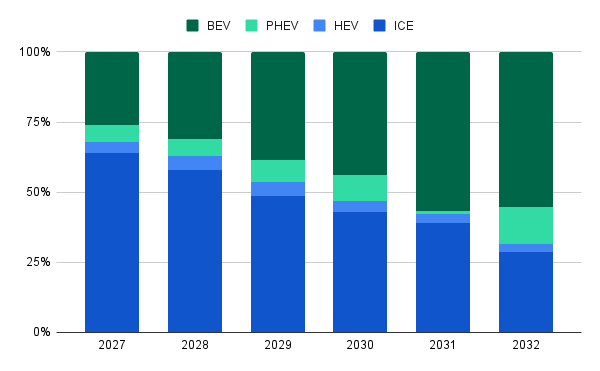

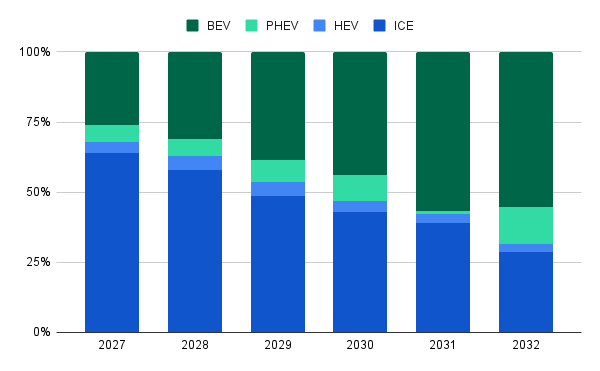

Because it’s up to the automakers to decide how to respond to these regulations, the exact impact on the speed of electrification remains to be seen. However, it’s estimated that these new standards will result in roughly 56% of new passenger vehicles nationwide being electric by model year 2030. Under that scenario, new car sales would look something like this over time.

In the graph above, ICE means “internal combustion engine”, HEV means “hybrid”, PHEV means “plug-in hybrid electric vehicle”, and BEV means “battery electric vehicle."

In the graph above, ICE means “internal combustion engine”, HEV means “hybrid”, PHEV means “plug-in hybrid electric vehicle”, and BEV means “battery electric vehicle."

Huge Public Health & Cost Benefits

These new standards will have a huge positive impact overall. In terms of emissions reductions, the Biden administration’s press release finds the new rules will avoid 7.2 billion tons of carbon dioxide emissions through 2055 and that compared to existing standards for model year 2026, the final 2032 standards “represent a nearly 50% reduction in projected fleet average GHG emissions levels for light-duty vehicles and 44% reductions for medium-duty vehicles. In addition, the standards are expected to reduce emissions of health-harming fine particulate matter from gasoline-powered vehicles by over 95%. This will improve air quality nationwide and especially for people who live near major roadways and have environmental justice concerns” (emphasis added).

In terms of cost benefits, the EPA anticipates $99 billion in annual benefits, including $13 billion in health benefits, $46 billion in annual fuel savings, and $16 billion in annual maintenance/repair savings. For a buyer, these standards are expected to save drivers an average of $6,000 over the lifetime of a new car.”

It’s worth taking a moment to highlight who these standards will benefit. There is strong support from public health experts for more stringent vehicle standards across the board. The American Lung Association, for example, advocates for strong national standards in its 2023 State of the Air report. More specifically, these standards will benefit communities that currently bear the worst burdens from vehicle pollution – and those communities are disproportionately communities of color and/or low-income. As GreenLatinos’ Sustainable Communities Program Director, Andrea Marpillero-Colomina, put it: “Pollution from vehicles disproportionately burdens Black and brown and low-income communities. These standards ensure that new car buyers have cleaner choices that cost less, and will lead to cleaner air for communities across the country.” She goes on to say the standards alone are not enough – we agree, and more on that later.

Impact in Massachusetts & Rhode Island

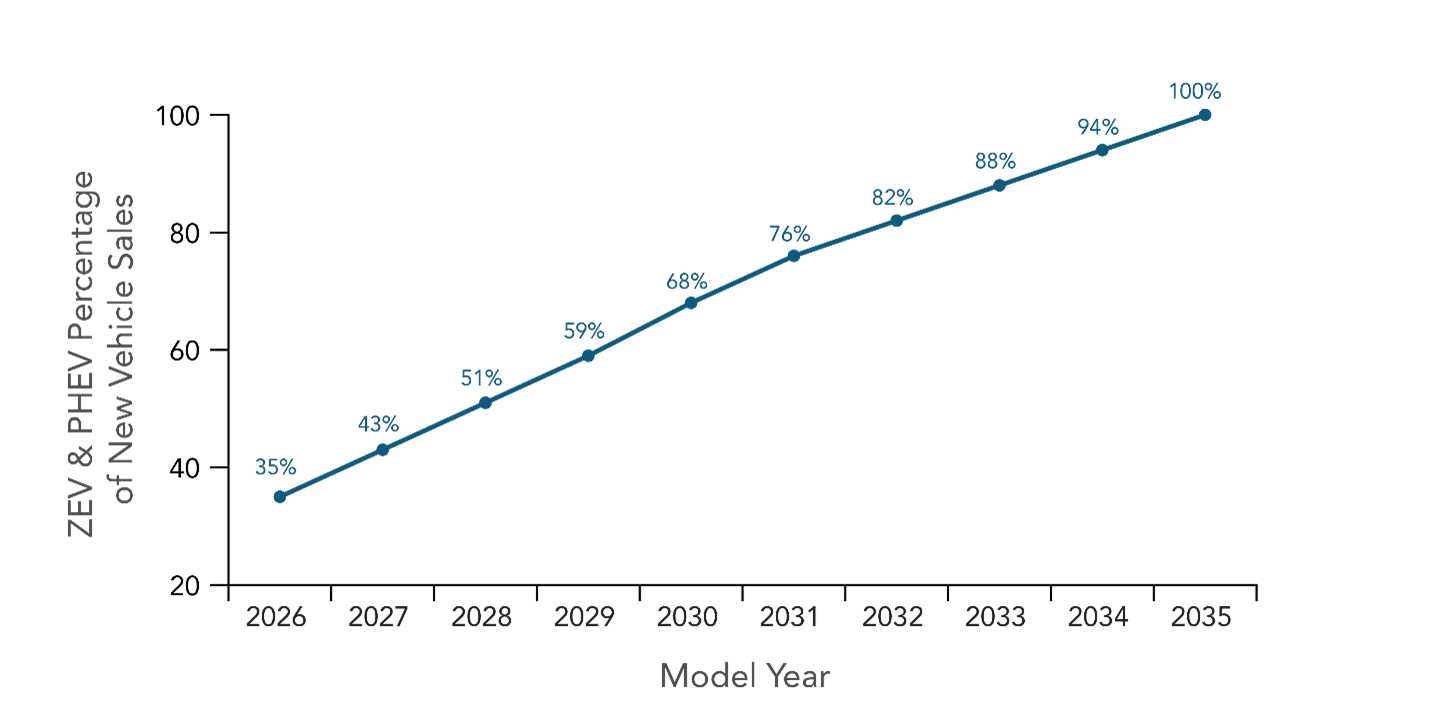

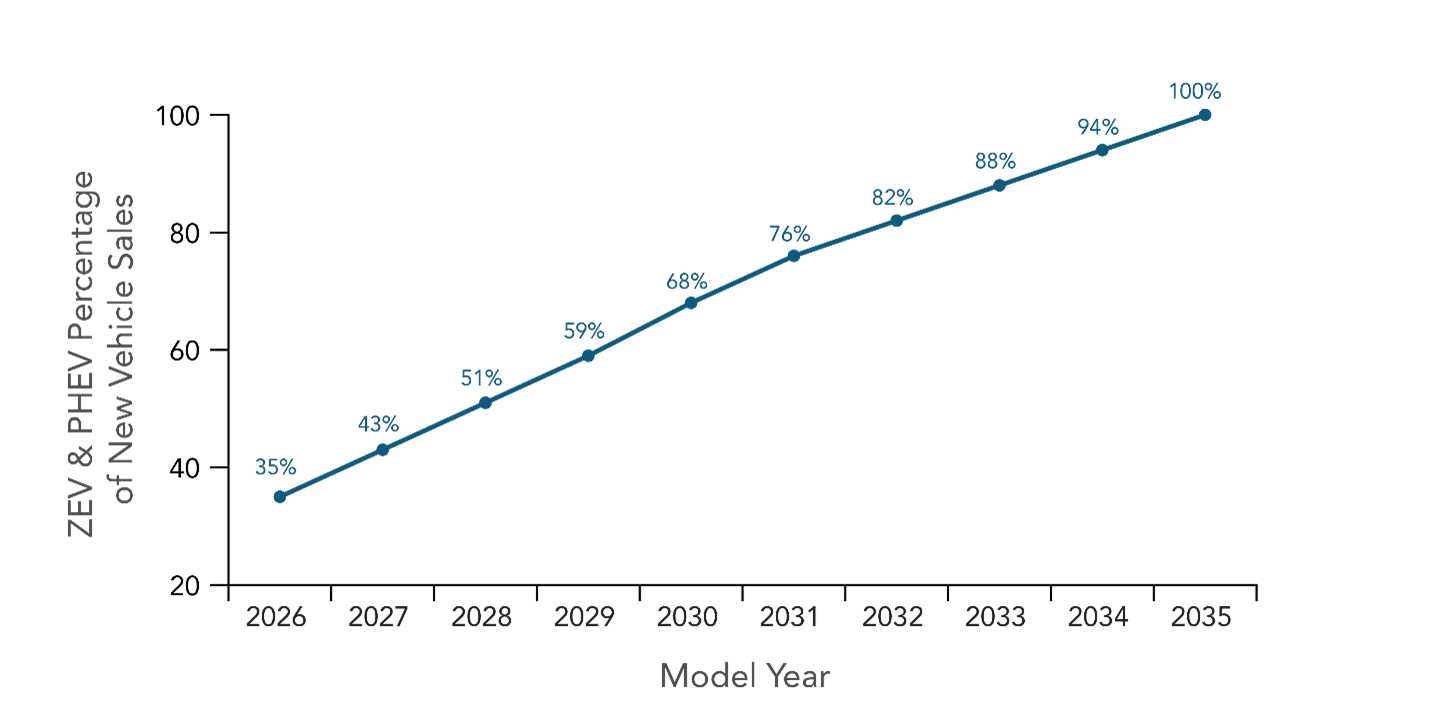

In Massachusetts and Rhode Island, these new federal standards mean it will be easier for the states to meet the required greenhouse gas emissions reductions in the transportation sector. Both states have adopted the Advanced Clean Cars II (ACCII) regulations, which require automakers to make an increasing percentage of the vehicles they sell in our two states electric over time, reaching 100% of new vehicle sales being electric by 2035.

Before these new EPA regulations were finalized, automakers had to comply with ACCII in the states that have adopted the standards: California, Colorado, Delaware, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and Washington, D.C.

-1.png?width=1000&height=671&name=These_are_the_states_where_carmakers_are_going_to_work_hardest_to_encourage_people_to_buy_electric_vehicles%20(1)-1.png)

Now, automakers have the whole US auto market to clean up on top of meeting ACCII requirements in that list of states. In other words, when an automaker is deciding where to make more EV models available, they’ll have double incentives to send them to markets like Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Selling more EVs in our two states will help them meet the ACCII standards and the overall EPA standards. We expect this to result in more choices and lower prices for consumers in our two states. (The Boston Globe has an excellent article on the topic here.)

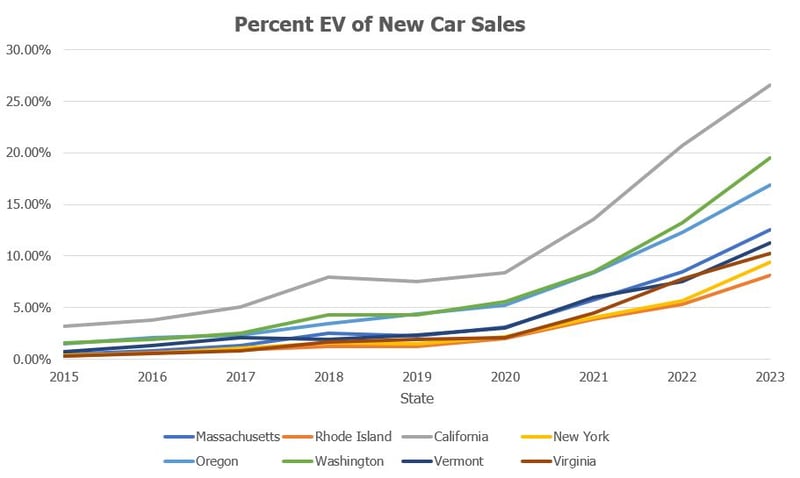

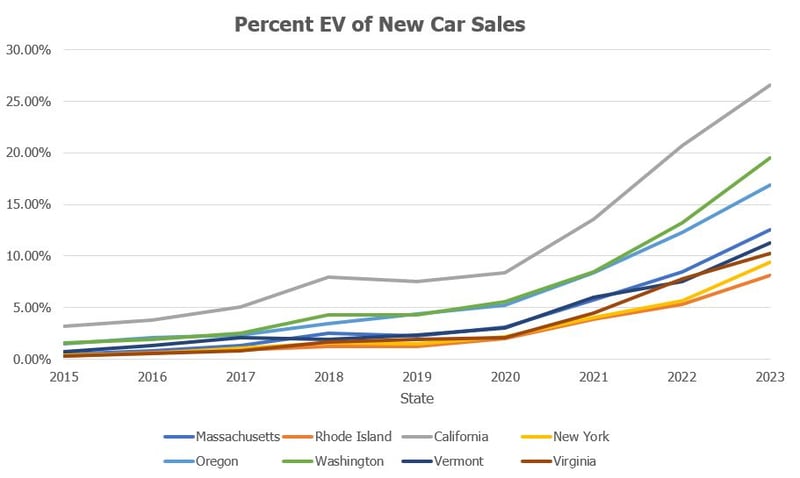

Here’s where some of the states that have adopted ACCII are in terms of the percentage of new vehicle sales being electric. (The data comes from the Alliance for Automotive Innovation’s EV Dashboard.) Note that California reached over 26% in 2023, that Massachusetts is behind Oregon and Washington at 12%, and that Rhode Island is the furthest behind, at only 8%.

When looking at this graph, it’s important to remember that the adoption of new technology does not happen linearly; the rate of adoption will increase over time. Bloomberg New Energy Finance has found that the tipping point is around 5%; countries across the world have jumped from 5% to 25% in just four years.

The combined effect of the EPA rules and ACCII is going to be felt more quickly than you might be aware. As a reminder, this is the rate of EV adoption in states that have adopted ACCII is illustrated in the graph below. Massachusetts will start with model year 2026; Rhode Island, with model year 2027.

The long and short of it is: yes, the adoption curve we need in the next couple of years is steep, but we can do it with a combination of (a) policies such as these EPA regulations and ACCII that set all manufacturers on a level playing field in terms of expectations and (b)supportive policies, such as EV incentives, the build-out of charging infrastructure, smarter rate design, and more.

What’s Next

The EPA’s draft regulations released last year were more stringent and the final regulations represent a compromise with carmakers and unions to allow a little more time to develop the market and build out the charging infrastructure we need. However, that compromise does not mean the standards will go unopposed. The Washington Post reports that “the American Fuel & Petrochemical Manufacturers (AFPM), an industry trade group, has launched a seven-figure campaign against what it calls a de facto ‘gas car ban.’” It’s likely that this battle will go to the Supreme Court. Buckle in for a bumpy ride.

In the graph above, ICE means “internal combustion engine”, HEV means “hybrid”, PHEV means “plug-in hybrid electric vehicle”, and BEV means “battery electric vehicle."

In the graph above, ICE means “internal combustion engine”, HEV means “hybrid”, PHEV means “plug-in hybrid electric vehicle”, and BEV means “battery electric vehicle."-1.png?width=1000&height=671&name=These_are_the_states_where_carmakers_are_going_to_work_hardest_to_encourage_people_to_buy_electric_vehicles%20(1)-1.png)

Comments