There are Three Ways to Buy Green Electricity – Two Are Good and One is Bad

This is an update from previous blogs on the subjects covered here.

Have you recently received salespeople at your...

In the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, about 85% of the population is served by investor-owned electric utility distribution companies - Eversource, National Grid, and Unitil. By law, their customers have three options for how they would get their electricity supply. The first option is to stick with the utility’s Basic Service. The second is to select, by yourself for just yourself, a “competitive power supplier”. And the third is to receive the supply service from a community’s municipal aggregation program.

Although municipal aggregation has proven itself to be the superior option for consumers both economically and environmentally, Massachusetts government, especially the Department of Public Utilities, has failed to support the model to the extent necessary to achieve important policy goals.

In February, we released the 2nd edition of our report on Green Municipal Aggregation in Massachusetts. We lay it all out there. Aggregation is better than utility Basic Service because:

Aggregation is far better for consumers than competitive power suppliers who sign up customers one at a time. Don’t take our word for it. Attorney General Maura Healey has commissioned two studies detailing how most households that choose competitive suppliers pay more than if they were on Basic Service – and the ones who get ripped off the most are low-income, elderly, and people of color.

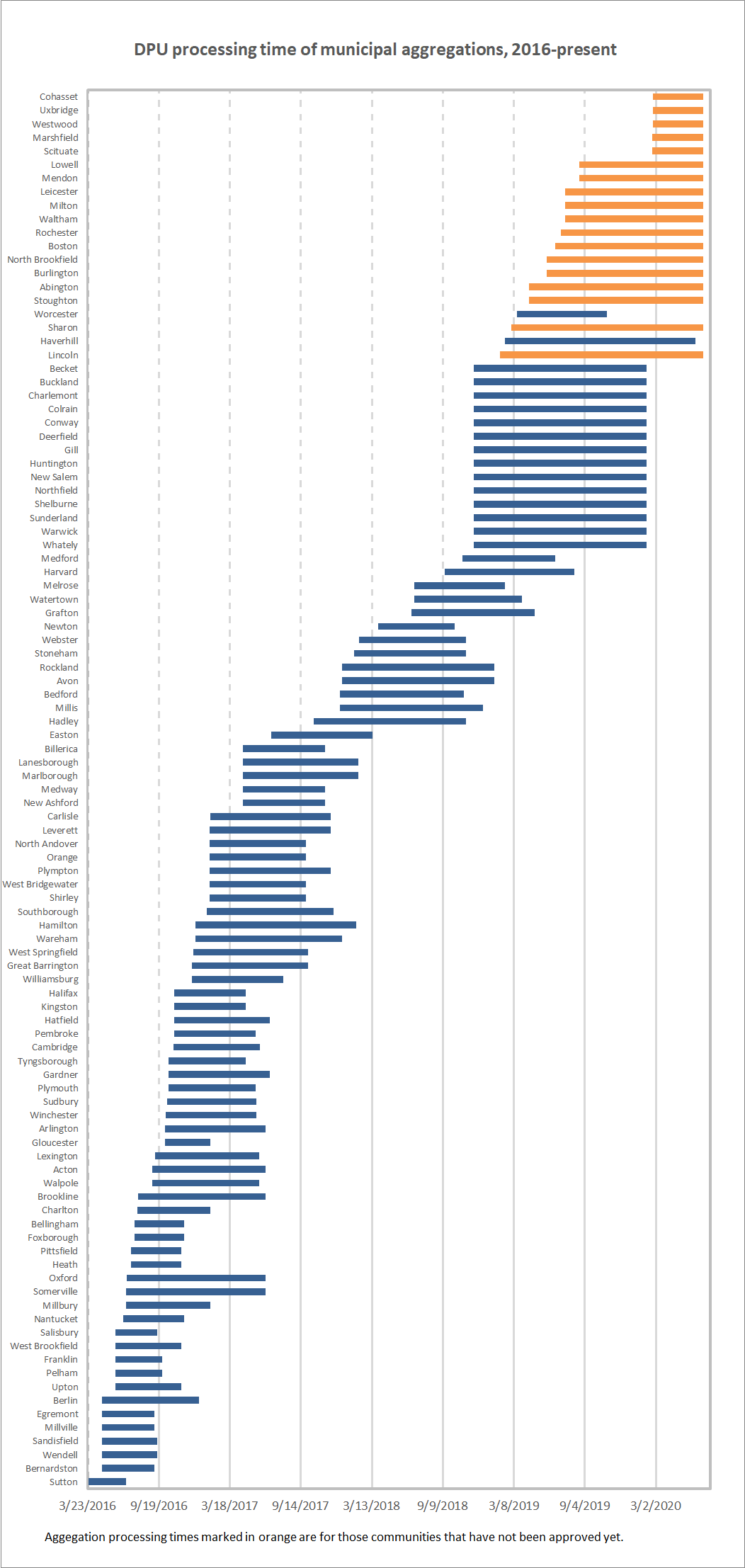

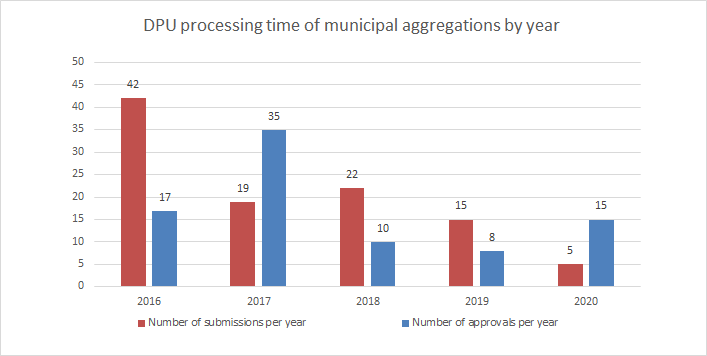

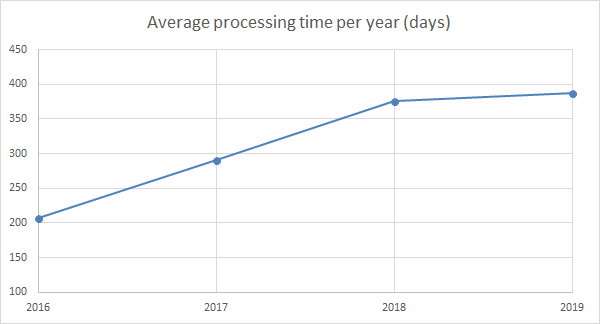

According to a 1997 state law, any municipality wishing to start up an aggregation has to get their plan approved by the Department of Public Utilities (DPU). By our analysis, the DPU has been taking more time than ever to approve such plans. Boston, Waltham, and several other communities have been waiting a year, which is par for the course since mid-2017. This is up from the 207 days to approve plans that were filed in 2016. In our view, 207 days is still too long, but that was better than where we are now.

Honestly, we don’t know why the DPU is so slow on these plans. We do know that the DNA of these plans is 80% or more the same in every one. There are subtle differences among them; none that should require a year’s worth of review. Bear in mind, that since 1997, about 160 communities have already run the gauntlet. So it’s not like DPU has not seen these things before.

And here's an important point if democracy matters: All of these plans went through a local approval process. Depending upon whether the community is a city or town, chief executives and legislative bodies had to vote after giving the public an opportunity to speak on the subject. After local approval, the plans had to be signed off by the Department of Energy Resources before getting a docket number at the DPU.

We have a climate crisis and the Commonwealth’s Global Warming Solutions Act requires the reduction of greenhouse gases. A huge amount of planning and discussion is going on all the time about how to achieve that, but progress has been slow. Municipal aggregation offers an easy (other than with respect to the DPU), voluntary, way to put points on the board.

By the way, Massachusetts also has a Green Communities Act which is about helping cities and towns go good things. Is there anyone in state government who can connect these dots?

Putting the planet aside for a moment (gulp), when the AG’s data shows how consumers are getting bled by parasitic competitive power suppliers and when our data shows how aggregation saves money, why isn’t the DPU making aggregation approvals a top priority? Here’s what their web site says:

The mission of the DPU is to ensure that utility consumers are provided with the most reliable service at the lowest possible cost, along with the protecting the public safety from transportation and gas pipeline-related accidents, overseeing the energy facilities siting process, and ensuring that residential ratepayers' rights are protected (emphases added).

Aggregation is a proven model that is not getting the governmental love it deserves. We call upon Governor Baker, the legislature, Attorney General Healey, and most of all – the DPU – to act in support of the cities and towns that are trying to do the right thing for their constituents and the climate.

This is an update from previous blogs on the subjects covered here.

Have you recently received salespeople at your...

We're excited to announce the start of something good in Rhode Island. Seven cities and towns have adopted “green...

Comments