Energy efficiency has been a key climate mitigation strategy in Massachusetts and Rhode Island - reducing emissions, saving dollars, and driving economic development. Recent regulatory and policy updates are changing the way decision-makers think about efficiency and the way our utility-run programs account for the many benefits of and opportunities to leverage our cheapest, most abundant energy resource. Here we provide a brief status update on planning in both states.

Our utility-administered gas and electric efficiency plans have big implications for energy costs and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in each state going forward. They provide a window into what’s going well—and not so well—in our efforts to meet ambitious climate goals in the next decades.

In Massachusetts, implementation strategy for these plans is detailed in three year increments. Before the end of October, the Energy Efficiency Advisory Council (EEAC) will vote to adopt or reject the 2019-2021 Three Year Efficiency Plan (3YP).

In Rhode Island, strategy is similarly detailed in a three year plan, but implemented in one-year plans. The body equivalent to the EEAC is the Energy Efficiency and Resource Management Council (EERMC). On October 4th, it voted to approve the 2019 Program Plan.

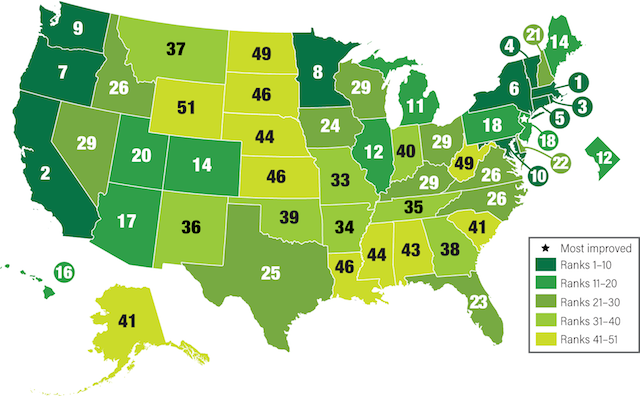

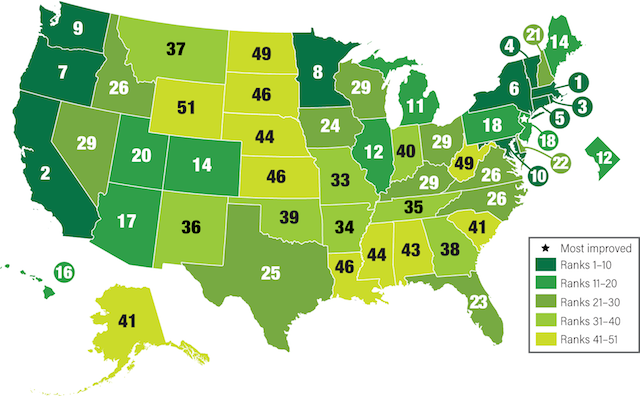

Efficiency serves consumers in Massachusetts and Rhode Island well, acting almost invisibly to reduce emissions, cut energy costs, and make our homes and buildings work better. For over a decade, these programs have consistently ranked top in the nation.

The ACEEE 2018 state efficiency rankings were announced on October 4th: Massachusetts (#1) and Rhode Island (#3) are leaders again.

Traditionally, “energy efficiency” has been defined by initiatives like LED lighting, home insulation, and efficient appliances, but efficiency is evolving. In addition to deploying proven measures, today’s programs are increasingly viewed as an avenue to support innovation and to advance new technologies capable of significantly reducing our reliance on fossil fuels, including electric vehicles, demand response, energy storage, and electric heat pumps.

Recent regulatory and policy changes in Massachusetts and Rhode Island are enabling these states to leverage new technology previously excluded from energy efficiency programs, in part to deliver deeper emissions reductions. These opportunities have been modestly reflected in the latest efficiency plans.

MASSACHUSETTS

The April 2018 draft of Massachusetts’ 3 Year Plan lacked detail and strong targets across the board, especially for demand response (Active Demand Management) and strategic electrification. It was a disappointing proposal, to be sure. The utilities were subsequently pressured to provide more in the September draft. This latest version includes some modest improvements to the plan – a commitment to marketing and outreach in multiple languages, no-cost weatherization for moderate income customers and a bigger landlord incentive intended to benefit renters - but it is deficient in four key ways.

1. Low savings goals. The savings goals proposed in the September draft plan are not only lower than what the program administrators have already demonstrated they are capable of achieving, but they are also significantly lower than what consultants to the EEAC have recommended is achievable.

2. Enhanced incentives for gas conversion. New to this plan is the ability to use energy efficiency funds to switch from one fuel to another, including a heat pump. Converting from oil or propane to fracked gas using EE funds: that is disconcerting. Efficiency dollars should be invested in ways that accelerate electrification of home heating and cooling and not in ways that detract from proven measures like weatherization and lighting, or that increase our consumption of gas.

3. Failure to account for costs to comply with state climate mandates. Relying on energy efficiency to cost-effectively reduce demand and reduce emissions, means that doing so in other ways or in other sectors may require less costly measures. The September draft acknowledges that nearly $1B more in benefits would be realized if program administrators (i.e. investor-owned utilities and the Cape Light Compact) were to use the value for compliance with emissions reductions mandated by the state’s Global Warming Solutions Act (GWSA). Curiously though, and without justification, the plan does not account for the Massachusetts-only value, an additional $35/ton of carbon that was determined as part of a DOER-commissioned study in which the program administrators participated.

4. Unwarranted increases in proposed performance incentives. The program administrators have proposed lowering the threshold that must be met in order for them to earn performance incentives. At the same time, they have proposed increasing the amount of the incentives to be paid out if thresholds are met. And nowhere have they committed to tying incentives to metrics that would induce the types of program delivery that we and others have been seeking for a decade – particularly, better service provided for low-to-moderate income customers, especially renters.

RHODE ISLAND

Rhode Island's 2019 Annual Energy Efficiency Plan goes farther than Massachusetts’ Three Year Plan in some key areas. Last year, the Ocean State began to incorporate environmental goals into its measure of the cost-effectiveness of energy efficiency. Other highlights include:

1. Equal efficiency program access, regardless of home heating fuel. Whether you heat with gas, oil, or electricity, Rhode Island’s efficiency programs can serve you.

2. 100% landlord efficiency upgrade costs covered.This adds a necessary incentive for landlords to make efficiency upgrades to units that they rent out.

Despite these highlights, though, there is still opportunity to take the Rhode Island plan further as it is implemented.

A strong efficiency plan would set ambitious targets, outline a clear plan and timeline for implementation, better incorporate carbon emissions reductions into cost effectiveness and performance incentives, and compensate program administrators without needlessly burdening ratepayers. Furthermore, we cannot continue to support efficiency dollars going to gas heat when we need to be turning our attention (and dollars) to electric heat. In Massachusetts, we’re advocating for a stronger final plan than the current one. In Rhode Island, we’re advocating for strong implementation that goes above and beyond an already strong plan.

Comments