This summer I moved from Massachusetts to Colorado and decided I was going to make the move in its entirety with just my electric vehicle (EV). I’ve had a 2019 Chevy Bolt for two years now and this was the longest trip I had ever done with it. It was a new experience for me, visiting places I had never been before, and it put the feasibility for long-distance road trips with an EV to the test. Acknowledging the gaps in public knowledge surrounding the logistics of driving an EV, never mind a 1,900 mile road trip, it was evident that sharing this experience could be useful to others. So here we go!

This summer I moved from Massachusetts to Colorado and decided I was going to make the move in its entirety with just my electric vehicle (EV). I’ve had a 2019 Chevy Bolt for two years now and this was the longest trip I had ever done with it. It was a new experience for me, visiting places I had never been before, and it put the feasibility for long-distance road trips with an EV to the test. Acknowledging the gaps in public knowledge surrounding the logistics of driving an EV, never mind a 1,900 mile road trip, it was evident that sharing this experience could be useful to others. So here we go!

Planning & Logistics

The trip from Massachusetts to Colorado is about 28 hours long, spanning nearly 1,900 miles. Taking I-90 into I-80, I decided to break up the trip into four segments at roughly 6-8 hours of driving per leg.

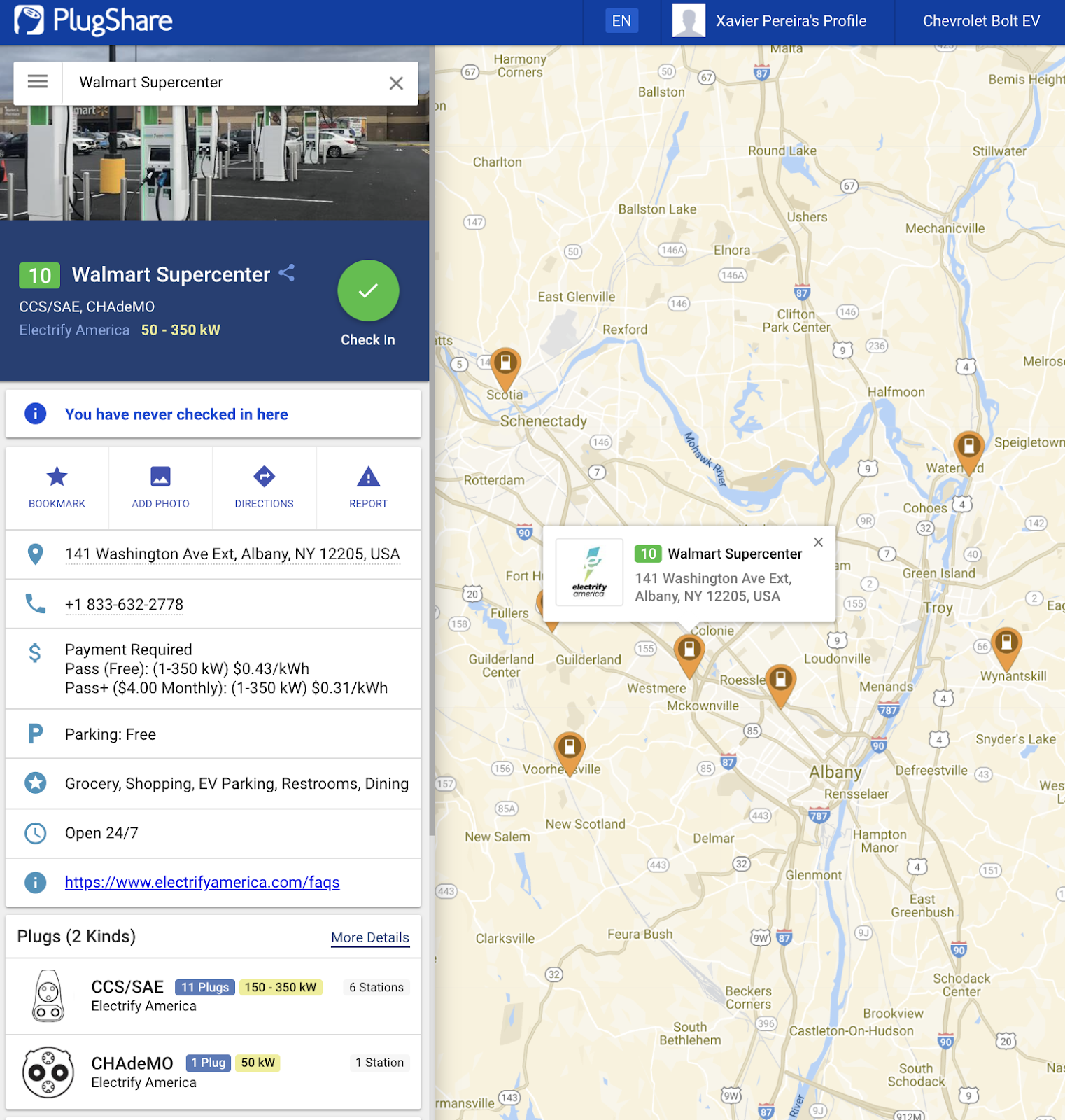

To plan out my route I used the PlugShare app’s route planning feature. The feature allows one to select a major highway between the starting point and destination, and select individual stations along the way. While doing so, it will show what stations are available near the limit of your vehicle’s range (my Bolt has a range of 259 miles). I’ll typically select one that makes sense based on the rating of the station, the availability, and what’s nearby. For this trip, I used only DC fast charging stations, which add about 90 miles in 30 minutes of charging (ish).

Figure 1. A screenshot from the PlugShare app. This was one of the DC fast charging stations I charged at along the way.

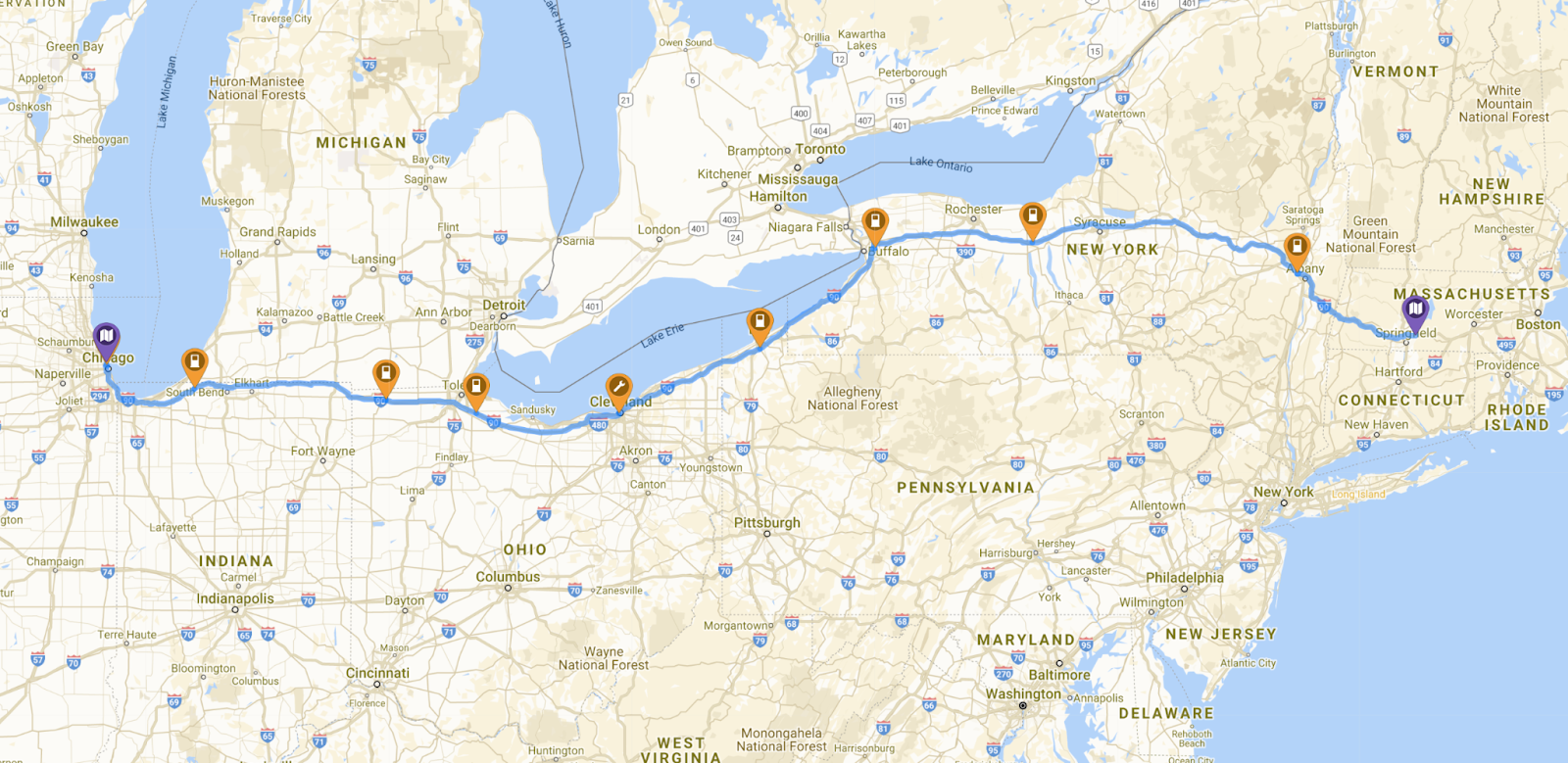

You chug along doing that until the whole route is planned, and it looks something like this:

Figure 2. The first two legs of the trip, starting from western Massachusetts to Cleveland, OH, and then from Cleveland, OH to Chicago, IL.

Above shows the first two legs of the trip. This route ends up being 13 hr 33 min of driving time, and 903 miles. With about nine stations along the way it’s around 100 miles per station. This breakdown can be found below in the Payment & Costs section.

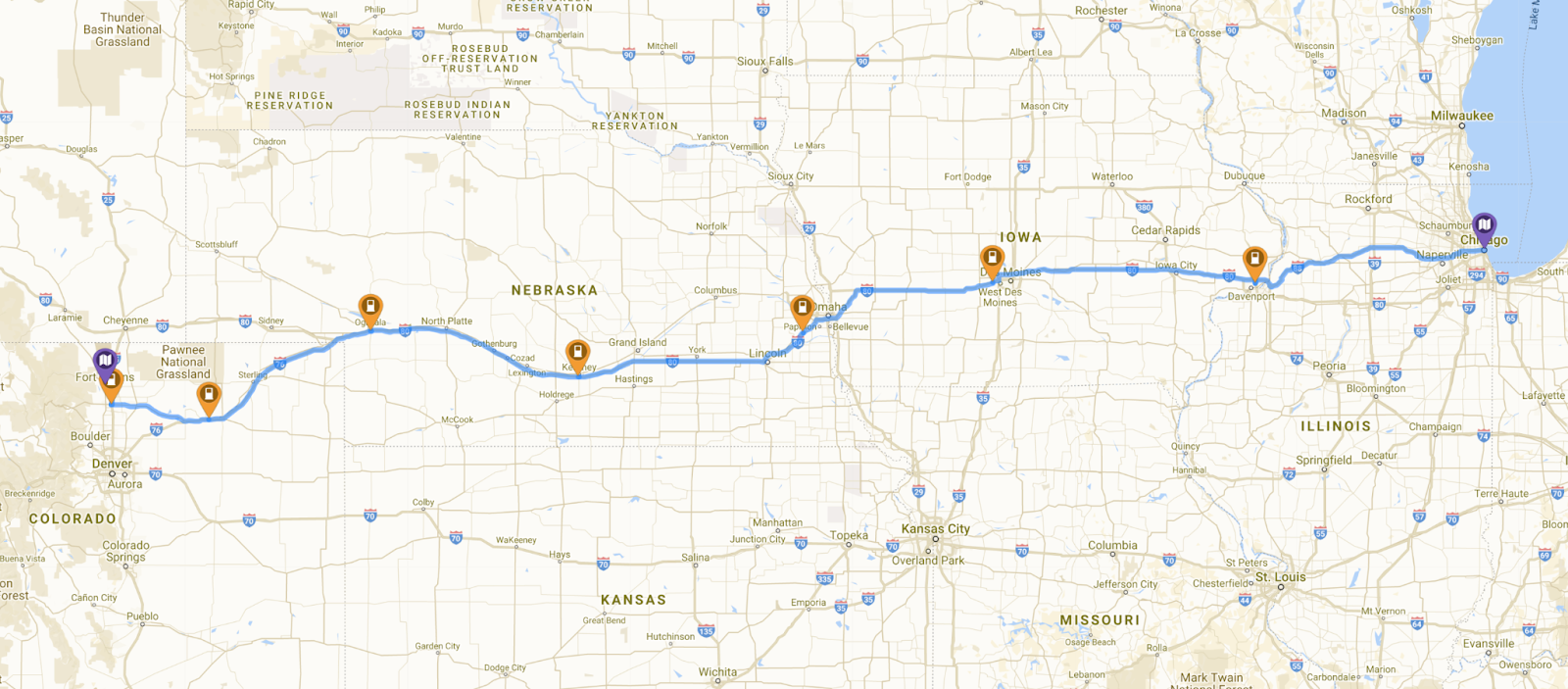

Below are the second two legs of the trip, from Chicago to Omaha, and Omaha to Fort Collins. This route goes on I-80 west most of the way, and then dips south catching I-76 just before Fort Collins.

Figure 3. The second two legs of the trip: from Chicago, IL to Omaha, NE, and then Omaha, NE to Fort Collins, CO.

Roughly, this plan in total equated to something like three charging sessions per day.

Additional note: I used the PlugShare app but there are a wide range of apps worth checking out when finding stations and route planning. These include Open Charge Map, ChargeHub, and A Better Route Planner. I like using the Plugshare app because of all of the individual station information it gives as shown in Figure 1, and the extensive ability to filter your search and find the stations that are the most applicable to your needs.

One might ask, if the range of a Chevy Bolt is ~250 miles, why charge every 100? There were a few reasons why I ended up doing so:

- There was one thing I had not realized when planning the trip- the extra weight of all of my belongings! This, combined with the fact that I was driving at highway speeds, had a bike mounted in the back, and that I had the AC on, greatly reduced my range to somewhere between 150-200 miles.

- Just for peace of mind, I kept a buffer and wanted to make sure I wasn’t planning on arriving at any station with less than 30 miles (I failed to keep this buffer several times).

- Third, because charging rates slow down significantly after 80% state of charge (SOC), for the sake of time I wouldn’t charge past that, and figured it would be more time effective to simply move on to the next station

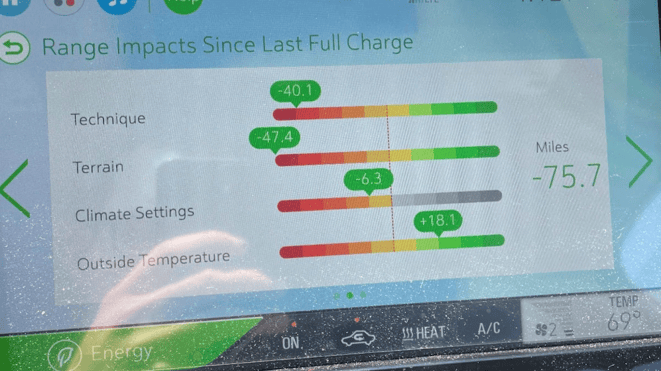

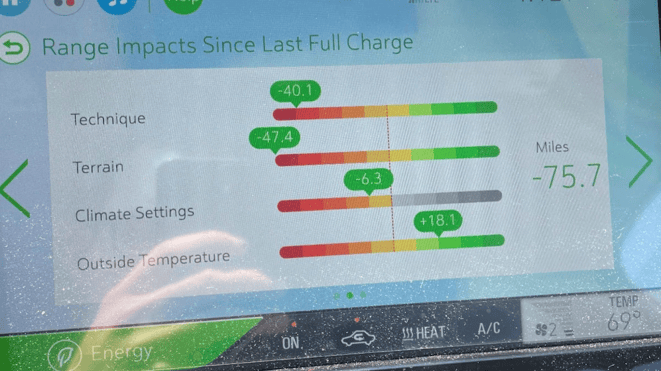

Figure 4. A photo of the Bolt’s touch screen displaying the factors that impact range.

This graphic on the console shows that overall my range was impacted by around 75 miles due to these factors. Driving at highway speeds is likely to be part of the “Technique” category, while I think the extra weight was lumped into both “Terrain” and “Technique”.

These three factors combined left me with about 100 miles to play with. And it turned out to not be a problem as the highways are very well lined with stations at rest stops and nearby towns often every 50 miles or so.

Payment & Costs

Once at the stations, the process for paying for them is straightforward. Most charging networks (ie. Chargepoint, Electrify America, EV Go) have their own app that you can create an account with, and then use Apple Wallet to quickly tap your phone and initiate the transaction. In addition, most have a card reader to swipe/insert a credit card. But the nice thing about having an account is that you can quickly access your charge history straight from the app. At a minimum, they will usually tell you how long you were charging for, the amount of energy (kWh) added, the total cost, and the peak output of the station during the session.

Looking at my charge history from Massachusetts to Chicago, I spent $118.54 on electricity and a total of 9 hours and 20 minutes charging. This came out to about $13.17 per session, where I added 29.4 kWh on average. For context, this would have cost me something to the tune of $91.68 for driving with an ICE vehicle. So the two modes were pretty comparable pricewise in this case. Generally speaking, it’s cheaper to drive a mile on electricity than it is to drive a mile on gasoline - in this case, driving on electricity costs a bit more because I relied on DC Fast Charging, where I’m paying not only for the power but for the convenience of charging quickly. For a full breakdown of the charge history and assumptions, click here.

Additionally, even though it came out a tad more expensive in this case, of course the difference in emissions over the course of the trip is the major benefit. For more information on how emissions differ between ICE vehicles and EV’s, click here.

Finally, I did not include a breakdown of the second leg of the trip, from Chicago, IL to Fort Collins, CO, as I actually drove while there was a promotion. It was the Fourth of July weekend, and Electrify America made all their DCFC stations free for the weekend! So while this was good news for me, it means that I don’t have any interesting cost breakdown to share, or even a charge history because the free sessions were never logged on my Electrify America account.

Experience & Public Perception:

Another takeaway from the table of my charging history is that charging with an EV forces you to take your time out there. On my drive from western Massachusetts to Chicago I spent about seven hours driving per day, and about 4.5 hours charging. While this seems like a lot of time charging relative to gas, think about the time spent during a road trip where the car is idly parked at a rest stop while one uses the restroom or grabs lunch. With an EV, there is no idling. At all times it’s basically either being driven or charging somewhere. So while my car charges, I would make a sandwich, grab snacks/ supplies at a nearby store, catch up with people, plan out the next stop, get out and stretch, read a book, and whatever else.

Figure 5. Left: My faithful companion on the trip was a bag of Portuguese rolls (papo secos), that I worked on every chance I had. Right: A lil PB&J I made with the last roll once I made it to the shores of Chicago.

Figure 5. Left: My faithful companion on the trip was a bag of Portuguese rolls (papo secos), that I worked on every chance I had. Right: A lil PB&J I made with the last roll once I made it to the shores of Chicago.

Figure 6. Left: A wrap that I had at one of the rest stations. Right: An EV Go station in Cleveland that was located next door to a lovely café, where I had breakfast before heading out.

Figure 6. Left: A wrap that I had at one of the rest stations. Right: An EV Go station in Cleveland that was located next door to a lovely café, where I had breakfast before heading out.

Figure 7. Examples of DCFC stations located at Walmarts. The unexpected peanut butter and chocolate of Electrify America and Walmart helped me out a great deal on this trip, which I had not anticipated.

Figure 7. Examples of DCFC stations located at Walmarts. The unexpected peanut butter and chocolate of Electrify America and Walmart helped me out a great deal on this trip, which I had not anticipated.

Another thing I’ve noticed is that out here in the west I’ve come across many more bad stations, or at least more instances of stations being down for extended periods of time (according to history on PlugShare). My current theory is because people use the stations less frequently, bad stations aren’t found, reported, and fixed very quickly. Currently the onus is on the users to report bad stations, otherwise they don’t get fixed. However, as more people use the stations, problems with stations will be detected and reported more quickly and there will be fewer stations down.

Figure 8. Examples of stations located at highway (I-90) rest stops.

Figure 8. Examples of stations located at highway (I-90) rest stops.

As a final note, during my travels I was always amazed at how many people would stop and ask me questions about the EV. On at least half of the stops I made I had a conversation with someone about EVs. At one stop in Ohio, I laid out on some grass nearby, but not super close to my car to read a book. Nevertheless someone still figured I was the one guy charging the car at the station and approached me with a few questions. So there are a lot of genuinely curious people out there, and the most common questions are, “How far can you drive on a single charge? How long does it take to charge? How much does it cost compared to gas?” One guy actually brought out a calculator and we did the math together. That time I wasn’t even parked, I was on my way leaving the parking lot, windows rolled down, and this guy yelled out for my attention!

Conclusion

So even at these early stages of the EV transition, I’d say the trip was mildly inconvenient at its worst. At its best, it forced me to be more present, enjoy the ride (and many papo secos), and connect with people along the way.

This summer I moved from Massachusetts to Colorado and decided I was going to make the move in its entirety with just my electric vehicle (EV). I’ve had a 2019 Chevy Bolt for two years now and this was the longest trip I had ever done with it. It was a new experience for me, visiting places I had never been before, and it put the feasibility for long-distance road trips with an EV to the test. Acknowledging the gaps in public knowledge surrounding the logistics of driving an EV, never mind a 1,900 mile road trip, it was evident that sharing this experience could be useful to others. So here we go!

This summer I moved from Massachusetts to Colorado and decided I was going to make the move in its entirety with just my electric vehicle (EV). I’ve had a 2019 Chevy Bolt for two years now and this was the longest trip I had ever done with it. It was a new experience for me, visiting places I had never been before, and it put the feasibility for long-distance road trips with an EV to the test. Acknowledging the gaps in public knowledge surrounding the logistics of driving an EV, never mind a 1,900 mile road trip, it was evident that sharing this experience could be useful to others. So here we go!

Comments