Electrifying Cars, Buses, and Trains

In Massachusetts and Rhode Island, emissions from transportation are our biggest climate problem. Although...

andAmelia Murray-Cooper

andAmelia Murray-Cooper

.png?width=600&name=Untitled%20design%20(20).png) Without question, the electric vehicle (EV) revolution is underway. At some point later this decade, we will see cost-parity, meaning that the upfront cost of an EV will be comparable to its fossil fuel-burning counterpart. Given that EVs cost so much less to operate and maintain, that point will be the tipping point. However, we have to reach that point and, for most consumers, state level incentives will be needed to spur adoption to the levels necessary for states to meet their greenhouse gas reduction targets for 2025 and 2030.

Without question, the electric vehicle (EV) revolution is underway. At some point later this decade, we will see cost-parity, meaning that the upfront cost of an EV will be comparable to its fossil fuel-burning counterpart. Given that EVs cost so much less to operate and maintain, that point will be the tipping point. However, we have to reach that point and, for most consumers, state level incentives will be needed to spur adoption to the levels necessary for states to meet their greenhouse gas reduction targets for 2025 and 2030.

It’s not easy for states to find money for EV purchase incentives. The Massachusetts program, MOR-EV, may expire on June 30 unless the governor and legislators can find new funds. Rhode Island has not had a purchase incentive for a few years and that has been a major reason why EV sales in the Ocean State are lagging. Governor McKee has proposed $1.25 million for next fiscal year and that’s welcome, but it’s only enough for 600 cars. So where can states look for sustainable funding that is also fair to people who won’t be buying an EV anytime soon? Feebates.

First, the idea is not ours. It’s been kicking around for a long time as a way to encourage consumers to purchase more fuel efficient cars. A feebate system has two parts:

Theoretically, a feebate could replace the sales tax, but we propose that it supplement the sales tax instead. Revenue from the state sales tax (6.25% in Massachusetts, 7% in Rhode Island) goes directly into the general fund to pay for the variety of items in the state budget. Fees paid into the feebate system would be earmarked specifically to fund rebates for purchases of electric vehicles.

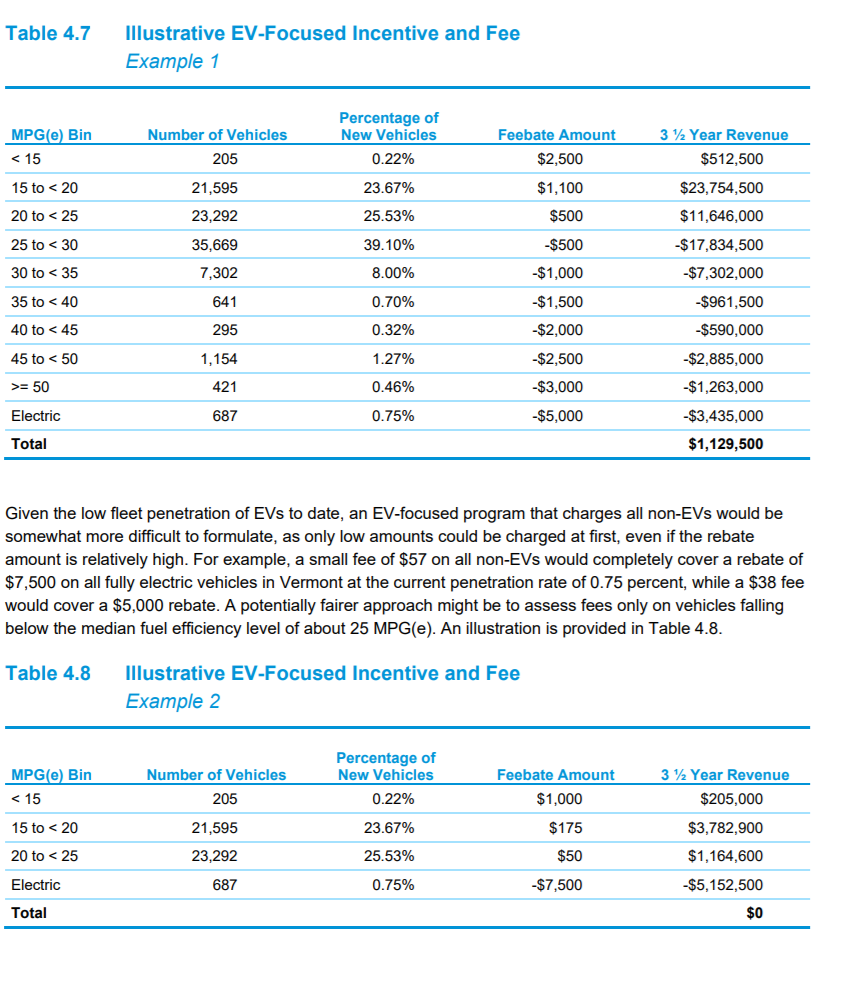

Jurisdictions around the world have implemented variations of the idea since the 1990s. France, Austria, Denmark, and Norway all currently have feebate programs in place. In Vermont, following the publication of the state’s Climate Action Plan, the legislature is currently considering the Transportation Innovation Act, which, among other things, calls for the implementation of a feebate structure.

The structure of a feebate system should be data-driven and designed to adapt to market changes over time. To design a program for a given state, we need data on the number of new vehicles registered by MPG each year. A report for the Vermont legislature included these hypothetical approaches, with fees that increase as MPG decreases and rebates as MPG increases. The highest rebates in this proposed structure would be for EVs.

Green Energy Consumers Alliance suggests a simpler approach:

Hypothetically, if 24% of new vehicles purchased each year get less than 20 MPG and less than 5% are electric in the first year of a feebate program, a $500 fee on low-mileage vehicles could provide funding for $2,400 rebates for EVs ($500 x 24 / 5). Such a feebate structure would send a strong signal on both sides of the equation while being far simpler to administer than either of the approaches illustrated above. (Note that the Massachusetts MOR-EV rebate is $2500. The current statute authorizing the MOR-EV rebate allows for rebates of up to $5,000.)

As EV adoption increases, the structure might have to be modified, perhaps by some combination of increasing the fee or decreasing the rebate. Another approach would be to increase the MPG threshold for what cars would trigger a fee over time.

A feebate that implements a fee on the purchasers of new vehicles that get less than 20 MPG would fall on the drivers of cars and light-duty pickup trucks.

What about folks who don’t drive?

What about folks who don’t drive? A feebate system will not impact people who do not drive directly in a financial sense, either positively or negatively. However, it will help to reduce emissions from light-duty vehicles, including those that harm public health.

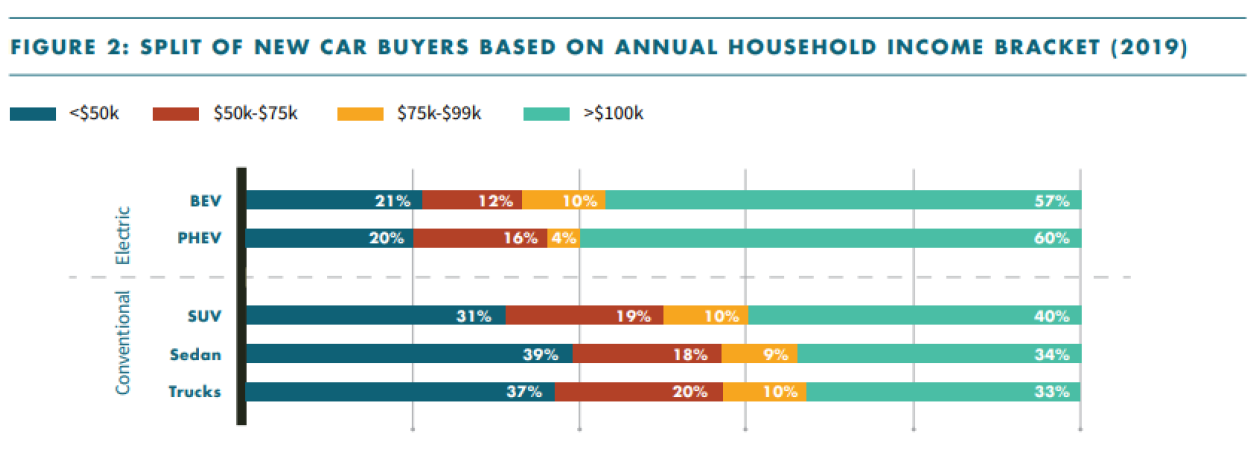

The fee portion of a feebate program as we are proposing it would primarily fall on high-income individuals. First, the fee would only apply to the purchase and registration of new vehicles; generally households purchasing new vehicles have incomes higher than the state median. This 2021 report from the Fuels Institute highlights that the largest portion of new car buyers in the United States are in households with an annual household income of $75,000 or higher.

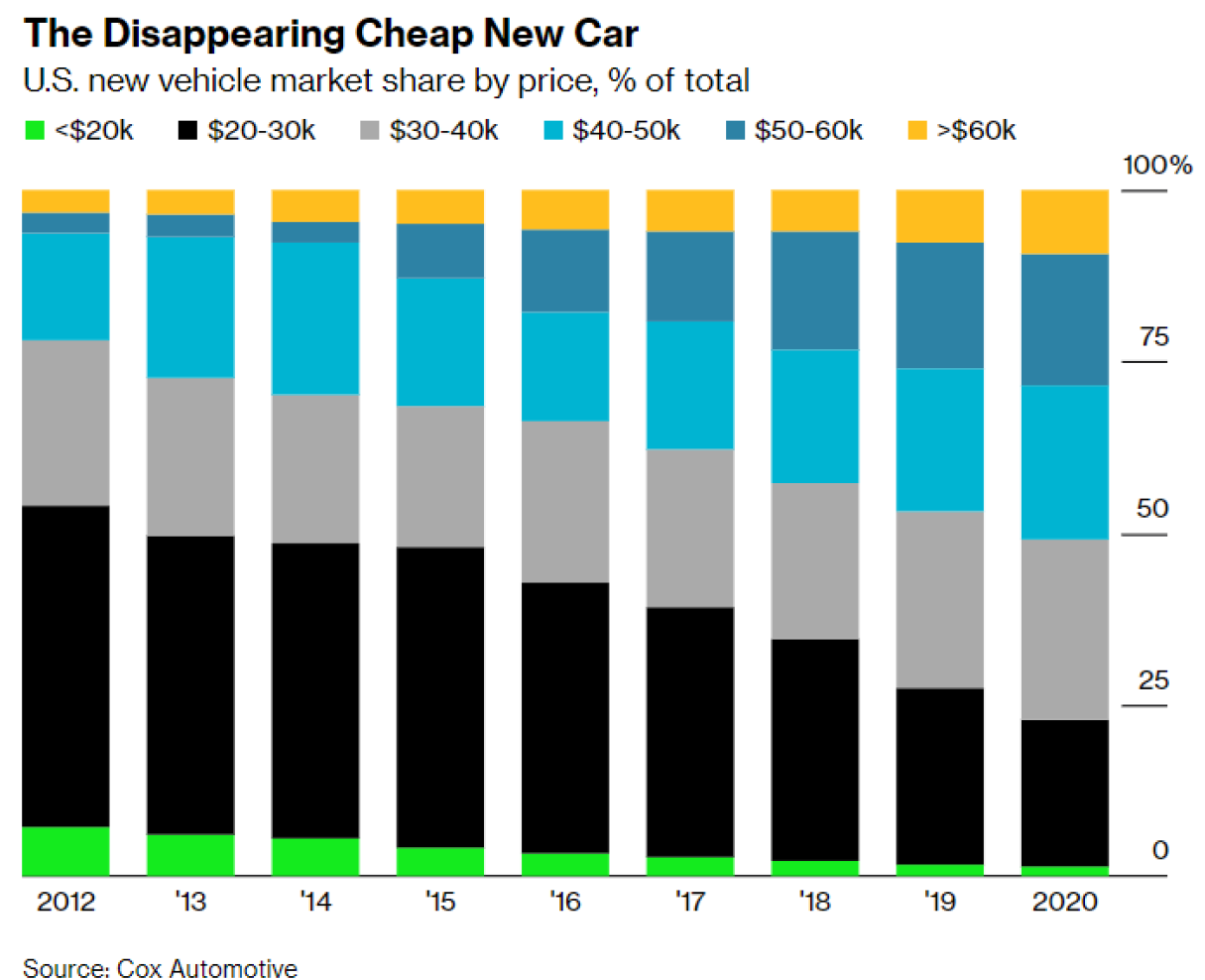

New cars have been getting more expensive over the past decade. At this point, more than half of new car sales in the US are on vehicles that cost more than $40,000.

In fact, consumers need an annual income of at least $78,000 to be able to afford a new vehicle. That’s well over the Mass. state median income, which is around $65,000 for an individual.

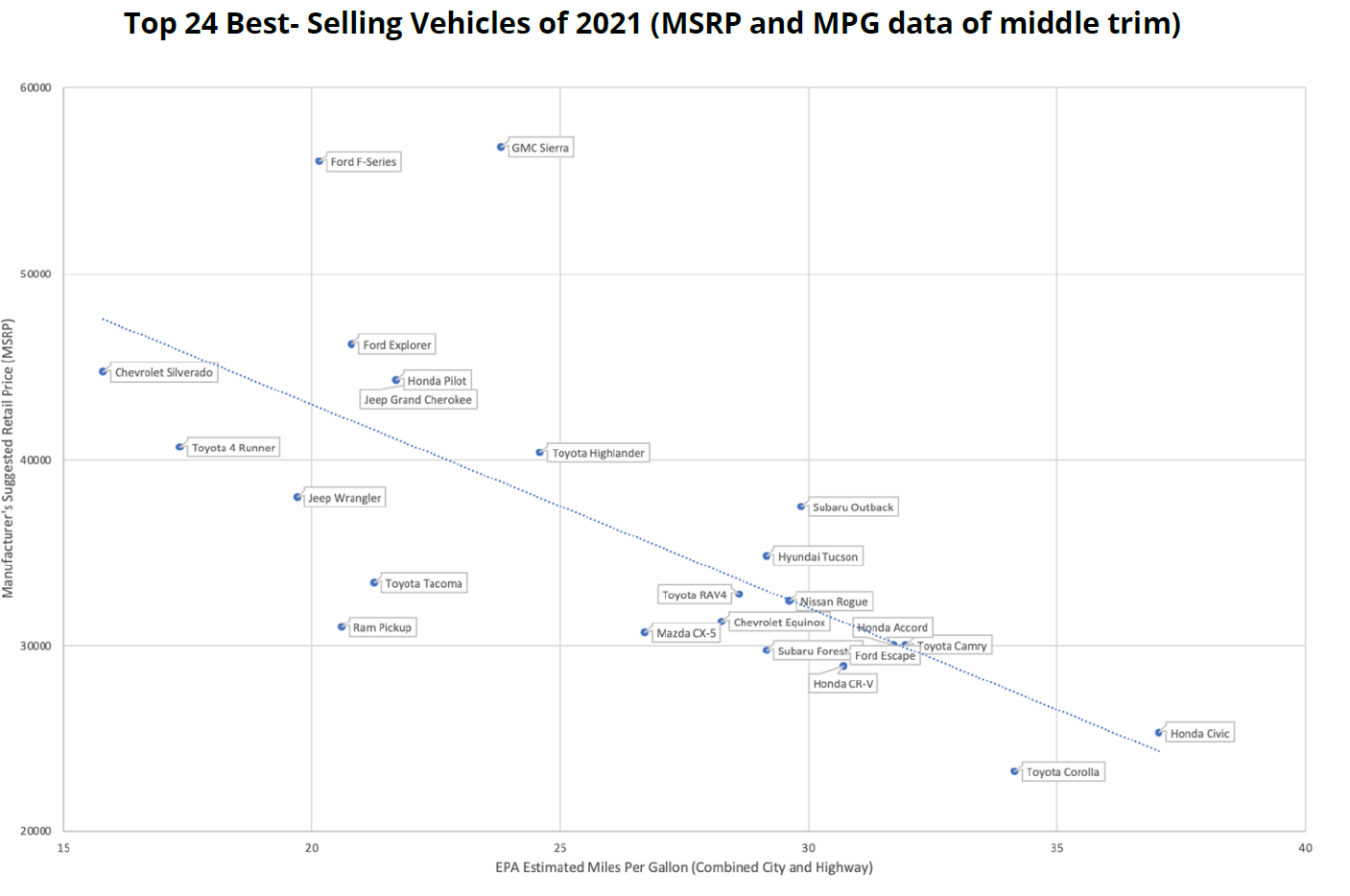

Even among new car buyers, those drivers opting for low-efficiency vehicles are most able to pay an additional fee. Our research has demonstrated that there is an inverse relationship between the purchase price of a vehicle and its miles per gallon. In other words, cars with high MPG are among the least expensive. Buyers of new, efficient cars would not pay a fee.

On the other end of the spectrum, cars with low MPG tend to be more expensive. So, the drivers that would pay into a feebate system are those already opting for more expensive new cars.

The fee within a feebate system as we are proposing would fall primarily on high-income new car buyers. Beyond the question of where the burden of the fee would fall, we believe a feebate system would be fair because consumers see the MPG label on the new cars they are buying. If they see a low MPG on a new car, they would be aware that it will consume a significant amount of gasoline and that it would incur a fee. Opting for a low-efficiency vehicle would be their choice. If they want to avoid the fee, there would be plenty of models that would be available.

The EV rebate can be targeted to vehicles selling below a certain price (say, $50,000, as the MOR-EV program is now) or it can be means-tested and offered to consumers with household incomes below the median. In other words, the feebate system can be designed so that consumers who would be paying for the fee would not be subsidizing the purchase of luxury EVs by high-income drivers.

Implementing a feebate program would free up scarce dollars for other worthy programs that could benefit underserved communities.

Both states need a funding source that is equitable and can be sustained for a few more years until EVs have reached cost-parity with gasoline powered cars.

If funds began to be larger than expenditures, the state would have several options:

We think the feebate idea is one worth pursuing as the legislature considers comprehensive transportation electrification legislation to meet the demands of a 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 (or 45% reduction in Rhode Island.)

Just a reminder, a few months ago, both Massachusetts and Rhode Island withdrew from the regional Transportation Climate Initiative before it even got started. And neither state has announced a “Plan B” for increasing EV adoption and reducing transportation emissions. Maybe feebates could be part of Plan B.

In Massachusetts and Rhode Island, emissions from transportation are our biggest climate problem. Although...

andAmelia Murray-Cooper

Our executive director, Larry Chretien, and professor Timmons Roberts wrote this article for the Brookings...

andAmelia Murray-Cooper

Comments