Electric Vehicles, Particulate Matter, and Public Health

We talk about electric vehicles (EVs) from a climate and consumer perspective all the time, but in honor of World...

Electrifying our vehicles is a critical tool for cleaning up the air we breathe and improving our public health. The public health effects of pollution from gas and diesel vehicles are widespread but are unequally centered in areas where Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) groups live. Electric vehicles (EVs) offer consumers cleaner and more efficient means of transport than gas cars.

We explored the connections between EVs and public health in-depth on our webinar with the help of three public health experts: Dan Fitzgerald, the Advocacy Director at the American Lung Association, Alyssa Benalfew-Ramos, former Chief of Policy at the Black Economic Council of Massachusetts (BECMA), and Dr. Ezra Cohen, a pediatrician at Boston Medical Center. We are continuing the conversation in this blog and in a recent podcast.

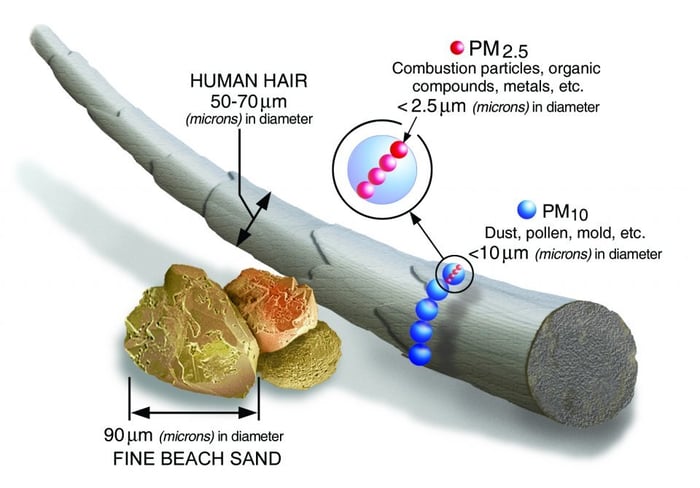

Vehicles produce many pollutants that harm human health, but one of the worst is particulate matter (PM). All road vehicles produce PM due to brakes, tires, and road wear. Gas cars also produce PM via combustion. We investigated particulate matter in this blog post; for the sake of brevity, we will describe two types of PM here. PM2.5 and PM10 are classified based on size: PM10 are particles less than 10 microns in diameter (some examples are dust, pollen, or mold), and PM2.5 are even smaller, less than 2.5 microns in diameter (tiny bits of metal or organic compounds).

How much PM is produced depends partially on a vehicle’s weight. While EVs tend to be heavier than gas cars due to the weight of the battery, studies continue to show that the absence of a tailpipe and less need for friction braking due to regenerative braking keep EVs’ PM emissions lower than gas cars overall. (If you want to learn more about the details of this, dive into this blog post.)

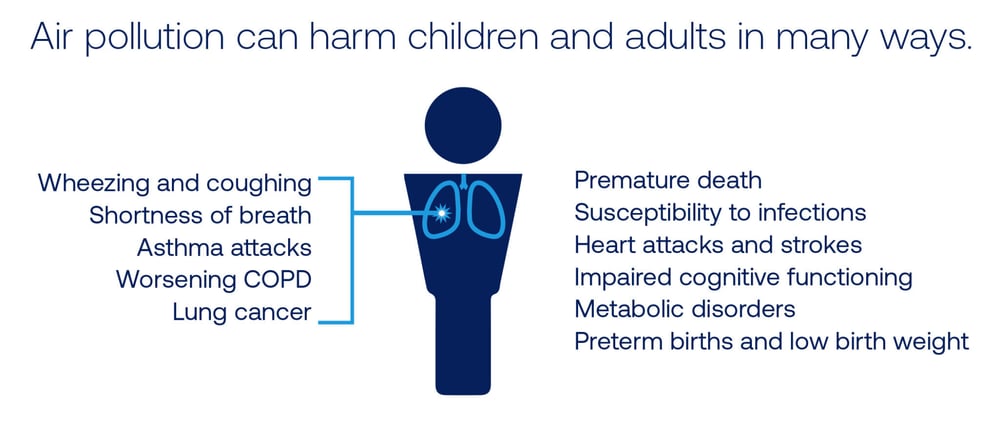

In our webinar, Dr. Ezra Cohen from the Boston Medical Center explained how PM enters our bodies: particulate matter penetrates the body through our air sacs, which transfer oxygen and carbon dioxide to our blood. Nitrous oxide and methane, two other pollutants that come from the burning of diesel and gasoline, can enter our bodies, as well. There is a big correlation between exposure to particulate matter and adverse health effects, namely, respiratory conditions.

American Lung Association: State of the Air Report (2025)

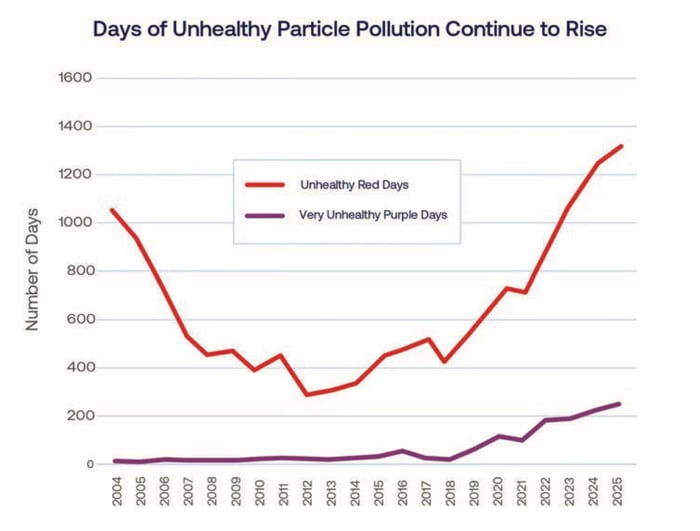

The American Lung Association highlighted in its 2025 State of the Air report that unhealthy air pollution from particulate matter continues to rise year after year, with 56.3 million people at severe pollution risk in 2024.

American Lung Association: State of the Air Report (2025)

Vulnerable groups, such as children and the elderly, people with underlying health conditions, pregnant women, and those who meet the national poverty definition, are exceptionally susceptible to developing negative health conditions. The report indicates a correlation between the following health conditions and residing in a polluted area: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), lung cancer, cardiovascular disease, and complications for pregnant women and their fetuses.

Several studies have drawn relationships between PM exposure and premature death, with older adults at the highest risk. A 2025 study by the Frontiers in Public Health cites air pollution as the fourth risk factor for premature death. Drawing from the at-risk population groups listed above, the American Lung Association’s 2025 State of the Air report observes greater hospital visits for cardiovascular disease (heart attacks or strokes) and COPD, increased severity of asthma attacks for children, and a higher risk of infant mortality.

Communities of color bear the brunt of the public health impacts of our reliance on gas and diesel vehicles because of historic and racist decisions around housing and transportation infrastructure. Redlining, a practice of housing discrimination in which federal agencies and mortgage lenders denied credit based on where people live, disproportionately affected black and brown communities. Redlining worked in tandem with discriminatory highway placement, supported by the Federal Highway Act of 1956, from which zoning policies divided and split up predominantly black and brown neighborhoods. As a result, Black and Brown communities are more likely to live near highways and transport depots still today.

Communities of color are more likely to experience higher rates of particle pollution and are disproportionately impacted by related health conditions. Several studies have observed this relationship; a 2024 study by the George Washington University Milken School of Public Health notes that communities of color experienced 7.5 times greater pediatric asthma rates and 1.3 times higher premature mortality rates than other communities. Another 2021 study by the EPA’s Center for Air, Climate, and Energy Solutions documents that people of color tend to live in places that have higher-than-average pollution levels from nearly all emissions sources, whereas White communities often live in neighborhoods with cleaner air. Lower-income groups often live in areas with high pollution rates and are vulnerable to related health conditions.

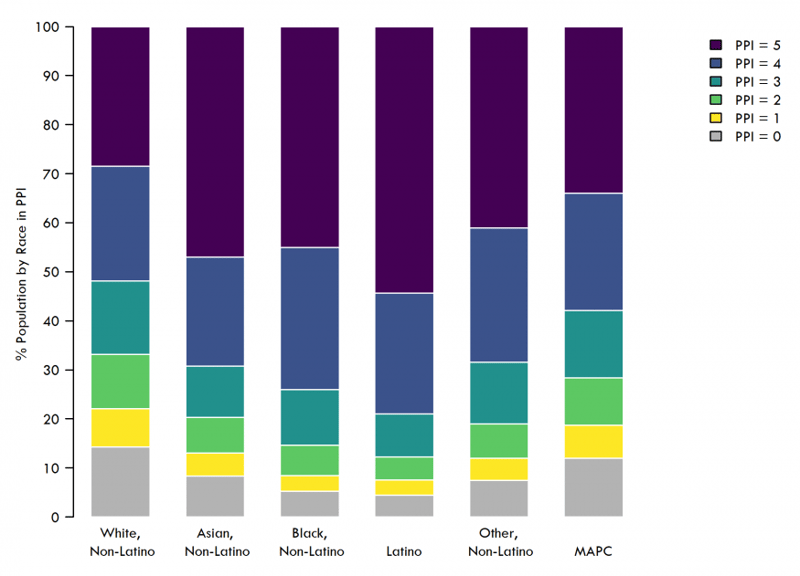

The unjust impacts of particle pollution exposure are felt in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. A 2020 study by the Metropolitan Area Planning Council (MAPC) creates a pollution proximity index (PPI) to measure pollution intensity and draw connections between neighborhood demographics and vehicle air pollution. The study indicates that 45% of Black and Asian residents and more than 50% of Latino residents reside in the highest polluted communities.

Areas with greater pollution have a PPI score of five and comprise the darkest portions of the map below. These areas are Greater Boston and major roadways.

.png?width=1000&height=468&name=Pollution%20Proximity%20Index%20(blog).png)

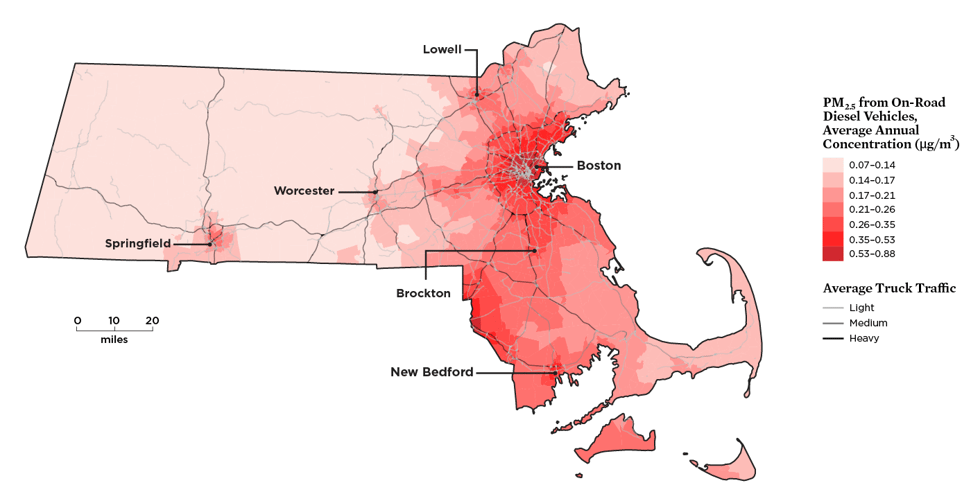

In Massachusetts, vehicle pollution is concentrated at transit hotspots. This list includes Mass Pike, I-93, I-95, and Gateway Cities such as Fall River, New Bedford, Brockton, Lawrence, Lowell, Springfield, and Worcester. The map below portrays the average annual concentration of PM 2.5 within the state’s transit hotspots.

Union of Concerned Scientists: Exposure to Diesel Particulate Matter in Massachusetts

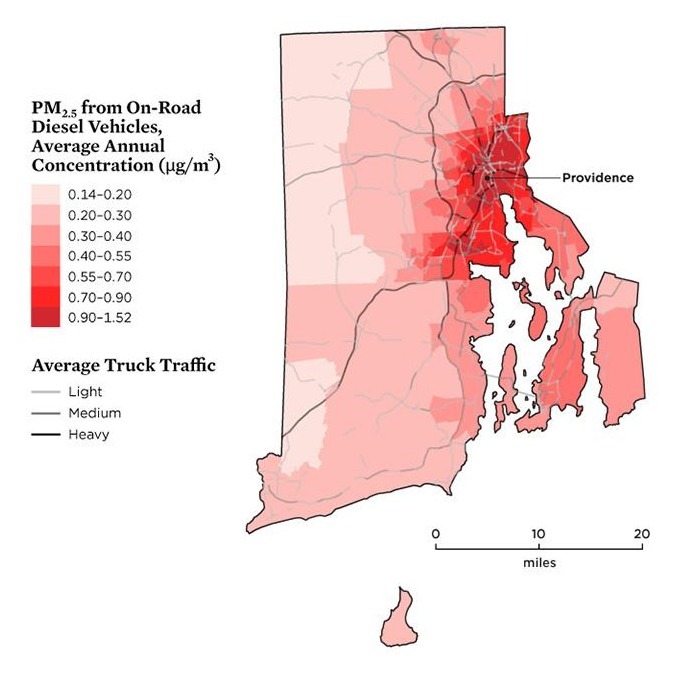

Similarly, most of Rhode Island’s vehicle pollution is present along transit corridors, like I-95 and I-195.

Union of Concerned Scientists: Exposure to Diesel Particulate Pollution in Rhode Island

City-wide real-time PM 2.5 concentrations can be seen in the graph below, thanks to Breathe Providence. The spread of PM 2.5 reflects city-wide disparities in tree cover, the I-95 road map, and census demographics. The East Side of Providence, a neighborhood that includes College Hill, retains less PM 2.5 than other neighborhoods. The East Side, which houses the most trees and one I-95 exit, is majority White and higher income, according to the 2020 Census. This suggests a correlation between PM 2.5 concentrations by population demographics and transit routes.

Breathe Providence: Fine particulate matter in Providence

Across both states, concentrated vehicle pollution overlaps with state-designated environmental justice communities. This further proves that particle pollution is an equity problem.

Learn more by listening to Alyssa Benalfew-Ramos’s presentation about redlining and vehicle pollution in Greater Boston.

Alyssa Benalfew-Ramos from the Black Economic Council of Massachusetts summarizes the bottom line well: “transitioning away from gas and diesel is one of the most direct ways to improve public health and address inequities.”

Widespread vehicle electrification is a critical tool to improve the air we breathe and our public health. Electric vehicles are better and cleaner for many reasons (check out this blog post for more information), and their market presence has significantly impacted the average fuel economy and average emissions of the vehicle fleet as a whole.

Making the switch makes sense for our health and economy. Dan Fitzgerald from the American Health Association pointed out that 100% electrification of passenger vehicles by 2050 could avoid 89,300 premature deaths, 2.2 million asthma attacks, and 10.7 million lost workdays, while saving $978 billion dollars in public health benefits nationwide. Massachusetts could save up to $14.7 billion dollars and Rhode Island up to $3.7 billion dollars in total health savings. Considering the environmental, health, and economic benefits of EVs, it is imperative that we make the switch.

We talk about electric vehicles (EVs) from a climate and consumer perspective all the time, but in honor of World...

A June 18 Boston Globe story, “If even the secretary of transportation won’t take the train, who will?” greatly...

Comments