Meeting climate goals anywhere, including Massachusetts and Rhode Island, depends upon electrifying everything – cars, space heating, water heating, stoves, and clothes dryers. Combustion has to be phased out. Federal and state purchase incentives for many of those items help level the playing field on an up-front cost basis. However, they do not address operating costs. To meet our climate goals, we must reduce the ratio of prices for electricity versus prices for fossil fuels – the Spark Gap.

What is the Spark Gap?

The Spark Gap is the ratio between prices for electricity and prices for fossil fuels. The higher the Spark Gap, the more expensive electricity is in relation to fossil fuels – and therefore, the harder it is to make a financial case to switch from something burning fossil fuels to something running on electricity.

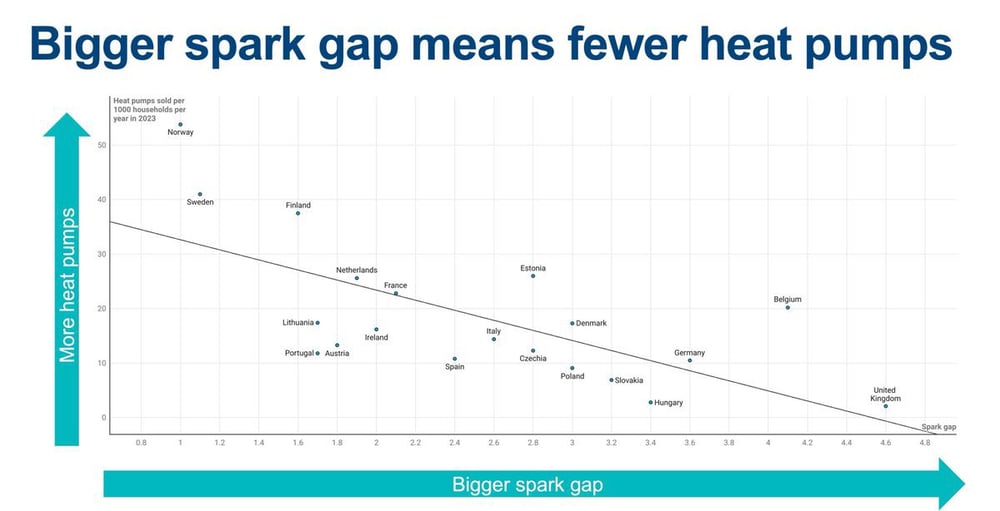

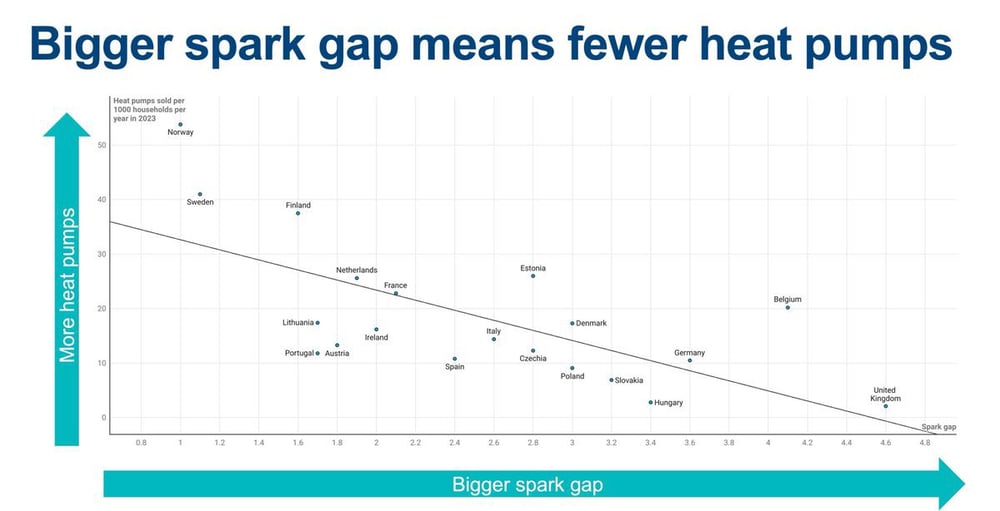

Jan Rosenow of the Regulatory Assistance Project and others have shown how European countries vary on heat pump adoption in correlation to the size of their respective Spark Gaps.

You can see that heat pump adoption rates are much higher in countries where the spark gap is smaller. This is common-sense economics, right? The less expensive electricity is in comparison to fossil-fueled heating, the more quickly people will make the switch to heat pumps. The same logic holds true in the United States and for other technologies, especially the ones that displace and use the most energy – heat pumps, water heaters, stoves, dryers, and cars.

Policy Implications

So, to speed the transition away from combusting fossil fuels to running everything on electricity, we have to reduce the Spark Gap. If we look at this purely mathematically, that can happen by reducing electricity prices, increasing fossil fuel prices, or both. Obviously, we want to do this in a socially just way – making sure that no one, especially people already struggling to pay for heat or electricity – is overly burdened by fuel costs. At Green Energy Consumers, we think it’s going to take a suite of measures. Here, in no particular order, is a list. Some of these policy options offer “twofers,” meaning they help close the Spark Gap while also supporting other policy priorities often mentioned in Massachusetts and Rhode Island.

Change How We Pay for Energy Efficiency

In both Massachusetts and Rhode Island, we have excellent energy efficiency programs that incentivize people to switch to cleaner alternatives, like heat pumps and electric dryers. It’s important to note here that every dollar we invest in energy efficiency in these programs results in more than a dollars' worth of benefit for all of us – spending this money is worth it, both for the environment and our pocketbooks! But those efficiency programs are funded in part by a surcharge on our electricity bills (in addition to a surcharge on gas bills). Every time we increase the energy efficiency surcharge to pay for more needed investments in electrification, we increase the spark gap and thereby decrease the financial case for making the switch. That’s counterproductive.

For example, in Massachusetts, if the Department of Public Utilities approves the $5 billion plan proposed by the electric utilities for energy efficiency programming from 2025-2027 (the Three-Year Plan for Energy Efficiency and Decarbonization), the surcharge on electricity will increase by over a penny from 2024 to 2027, to over four cents per kilowatt-hour. The major reason for the surcharge increase is to fund incentives for heat pump adoption. One might say, “It’s only a penny.” But this is on top of what are some of the highest electricity rates in the country. And every additional penny makes running a heat pump less economical.

Even if the 2025-2027 Mass Save plan is approved, it will enable less than half of the 100,000 heat pump installations that Massachusetts needs annually to get on track for its climate mandates. Is another electricity surcharge increase on tap for 2028?

A better way to fund incentives to consumers for heat pump adoption is by implementing a Clean Heat Standard (CHS).

A CHS would require heating energy suppliers to replace fossil heating fuels with clean heat over time, either by implementing clean heat or purchasing credits. Those credits could go towards enabling customers to weatherize or electrify through air-source heat pumps, ground-source heat pumps, or networked geothermal. (These same measures are what the efficiency programs support now, but not at the scale we need.) A CHS would support heat pump adoption and realize the benefits of doing so without raising the electricity rate.

The Mass. Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) has been working on regulations to establish a CHS for well over a year, yet the 328-page Three-Year Plan for Mass Save does not acknowledge the likelihood of DEP creating the CHS in 2025. The two programs can work well together, but only if designed together. We are participating in the approval process at the DPU to make this point. Specifically, we suggest that DPU approve the Mass Save plan for 2025 and withhold approval of 2026-2027 until there is a proper plan to integrate DEP’s CHS with Mass Save.

Rhode Island, unfortunately, has not yet begun any CHS process.

Reform Electricity Rates

In addition to changing how we pay for energy efficiency, both our states need to take a close look at electricity rates more specifically. How can we change how rates are structured to support electrification and protect consumers?

Massachusetts is taking some steps forward on this front.

- The DPU has approved a new heat pump rate for customers of Unitil who install heat pumps, which shifts the economics of heat pumps in a more positive direction by making lower electricity rates available during winter months. National Grid will soon follow suit, and we hope Eversource will follow shortly. Maine has had heat-pump-specific rates and leads on heat pump adoption within the US.

- Massachusetts has an Interagency Rates Working Group (IRWG) developing a plan to align electricity rates with the Commonwealth’s decarbonization mandates, both in the short and long term. We’ve been attending essentially all of the meetings of the IRWG and submitting comments.

Rhode Island should follow suit on both fronts. The Rhode Island Public Utilities Commission has an ongoing docket called the Future of Gas that is investigating how to manage the gas distribution system in light of the Ocean State’s Act on Climate. Most of the work has been focused on the gas system, but Green Energy Consumers has advocated for electricity rate reforms like those under review in Massachusetts. The Future of Gas will be greatly influenced by the future of electricity rates. The PUC has jurisdiction over both gas and electricity, so synergy is possible.

Accelerate the Depreciation of Gas Utility Assets

Currently, when the gas company invests in infrastructure, it is allowed to depreciate that investment over its expected lifetime and charge that to ratepayers each year of its lifetime. It does so on a “straight-line basis,” meaning each year’s depreciation is the same for a specific number of years. That could be the replacement of a pipe on your street, or it could be the cost to hook up a new customer. The lifetime of most of these investments can be quite long, certainly more than 25 years. But we only have 25 years before our whole economy has to be net zero. The mismatch has consequences.

To be clear, allowing a gas utility to depreciate an asset past 2050 is a subsidy. That asset would become a “stranded asset” that someone has to pay for. However, care must be taken to ensure that accelerated depreciation rules are written with the long-term interest of consumers in mind. There are ways to prevent the utilities from gaming the system. An outcome to avoid is having accelerated depreciation increase utility profits.

If we accelerate the period of depreciation so that every asset is paid off by 2050, it will raise gas rates until then but eliminate them after 2050. That is a two-fer. It will help close the spark gap and be fair on a generational basis. People who are living past 2050 should not continue paying for gas service they will not be receiving.

The sooner accelerated depreciation is put in place, the fairer it will also be for gas ratepayers as well. The additional cost will be spread across more therms of gas and more customers than if we procrastinate.

Revisit Every Policy Raising Electricity Rates

Your electricity bill shows the major categories of items that comprise electricity service. But within each category, there are many other items that add up. Some have been in effect for many years and for the most part, those items are beneficial. But it’s time to investigate whether they are all worthwhile given the current circumstances in which we are turning heavily towards electrification while at the same time trying to keep electricity affordable.

.jpeg?width=1000&height=388&name=wind%20and%20solar%20energy%20(stock).jpeg)

Green Energy Consumers hopes to find the time to dive into all the elements of electricity rates in the near future. For now, we suggest looking closely at some components of the Renewable Portfolio Standard. We strongly support the “Class I” standard, which brings new (built after 1997) wind and solar onto the grid. Class I is key to decarbonizing the grid. But there is also a Class II standard for renewable energy facilities that existed prior to 1998 and a Class II Waste-to-Energy standard that subsidizes trash incineration. And there is an “Alternative Portfolio Standard” that mostly supports combined heat and power projects (usually fueled by natural gas) and liquid biofuels. Other than Class I, the other standards ought to be evaluated on whether they are contributing to the state’s climate mandate enough to justify their impact on electricity rates.

Reduce Costs for Off-Peak EV Charging

Electric vehicles (EVs) are part of this picture as well. Right now, it’s cheaper to drive a mile on electricity than a mile on gas (not to mention lower maintenance costs), but lower overall electricity rates would help more people make the switch. And, as we’ve written before, increased EV adoption helps reduce overall costs.

Managed charging programs, which incentivize people to charge during low-demand periods when electricity is cheap and emissions are low, only further both trends.

Invest in the DPU for Smart Modernization

We have been told by the electric utilities and DPU that grid modernization investments will add to the electricity rate, but much is not yet clear. Heat pumps and electric vehicles will certainly add to power demand and there will be good reasons to make capital investments to the distribution system. But how much remains to be seen? If we can manage the load better, we can avoid some of the costs associated with new substations, transformers, and the like. Grid modernization investments will be presented to the DPU by the utilities for approval. Therefore, the DPU must have adequate staff, particularly engineers, accountants, and economists, to carefully evaluate the tremendous amount of utility requests that will be forthcoming over the next many years. A few million dollars in DPU staff could save us all tens and hundreds of millions of dollars in higher rates.

Ban Retail Suppliers & Promote Municipal Aggregation

In 2024, the Mass. State Senate passed legislation to ban predatory and greenwashing retail electricity suppliers. Studies have shown that these suppliers charge tens of millions of dollars per year more for electricity than supply offered by municipal aggregation and investor-owned utilities. Unfortunately, the Mass. House of Representatives took the side of retail suppliers. We will try again in 2025 to pass the ban, primarily for reasons of basic consumer protection and social justice. But it would have the added effect of reducing the Spark Gap.

Revisit the Utilities’ Return on Equity (ROE)

Electric utilities earn a return on the investments they make in infrastructure as approved by the DPU in Massachusetts and the PUC in Rhode Island. The ROE determines how much profit the utilities will make. As electricity usage grows and as infrastructure investments are made to accommodate that growth, the regulators ought to consider whether the same rate of return is warranted when the basis could potentially double. It should not be taken as a given that utility profits should double as we make the transition from combustion to electrification.

Shift Low-Income Assistance to the Electricity Rate

In both states, low-income ratepayers are eligible for a discount on their electricity and gas rates. Those of us who are not low-income pay slightly higher rates to offset the cost of the discount afforded to income-eligible families. Green Energy Consumers Alliance has always supported that policy, and we will continue to do so. However, given the imperative to shift consumers from fossil fuels to electricity, we are putting forward a new idea. That is, we propose moving the discount rate in part or entirely to the electricity rate and increasing the electricity discount for customers of gas utilities commensurate to the average household’s gas usage. Every gas customer also has electricity service and this would be one way to make that year-round electricity service more affordable overall and relative to gas service. People on such assistance would receive the same amount of benefit overall, but all or mostly applied to just their electricity bill.

It is also time to consider applying the dollars currently allocated to the Low-Income Heating Assistance Program (or Fuel Assistance), which provides financial assistance to income-eligible households to pay their bills for gas, oil, propane, or electricity (if they have electric heat), entirely to their electricity bill. Again, the same amount of benefit (and hopefully more), but applied just to their electricity bill.

The point is that with these changes, the consumer would not see the electricity rate by itself as a barrier to the electrification of any device. For the low-income population, we can make the upfront acquisition cost affordable, if not free, through complementary policies.

Closing Thoughts

Between now and 2050 (the sooner the better), consumers are going to have to make decisions on how they heat the space they live in, how they heat water, how they cook, and how they dry clothes. That’s four decisions per home. On top of that, there are 1-2 cars per home on average. That’s a lot of decisions and they all hinge somewhat on the Spark Gap.

.jpeg?width=1000&height=388&name=wind%20and%20solar%20energy%20(stock).jpeg)

Comments