Recent Gas System Failures remind us that Gas Isn't Cheap

National Grid trucks line the street outside of Newport Fire Department Headquarters (Station One). Thousands of...

Carbon Free Boston, the latest in a series of climate action reports released in Massachusetts, further affirms that there are clear steps we should be taking now to mitigate climate change. The challenge remains in turning studies to action.

Carbon Free Boston (CFB) explores strategies the City of Boston could employ to tackle emissions from transportation, buildings, waste, and energy and to achieve carbon-neutrality by 2050. This requires three necessary and familiar steps:

Released in late January by the Boston Green Ribbon Commission, the CFB is the first of three designed to inform the 2019 update to Boston's Climate Action Plan and hopefully spur immediate action. Related technical and social equity CFB reports are due to be released in March.

In the 10 years since the Global Warming Solutions Act (GWSA) was passed, Massachusetts has made modest progress reducing statewide emissions. These gains have been largely driven by successes in two sectors: buildings and electricity supply. However, emissions from the transportation sector have increased in that time, contributing to a steeper climate compliance hill than was perhaps anticipated back in 2008.

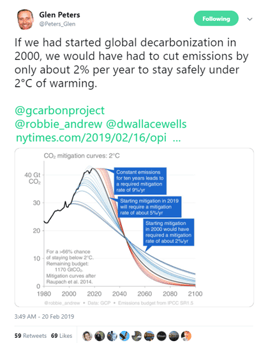

By our math ( and we're hardly alone on this), and assuming Massachusetts meets its 2020 mandated greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction of 25% below 1990 levels, we'll then have to reduce emissions more than 2% per year to meet the the state's 2050 mandate of 80% below 1990 levels. Even more aggressive annual reductions will be needed to achieve carbon-neutrality in the same period of time.

and we're hardly alone on this), and assuming Massachusetts meets its 2020 mandated greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reduction of 25% below 1990 levels, we'll then have to reduce emissions more than 2% per year to meet the the state's 2050 mandate of 80% below 1990 levels. Even more aggressive annual reductions will be needed to achieve carbon-neutrality in the same period of time.

Despite planning, we increasingly find ourselves behind the eight ball and need to get cracking on climate action – city by city, state by state. As the Commonwealth's largest city, actions taken in Boston to substantially reduce GHG emissions could greatly influence the state's overall efforts to do the same.

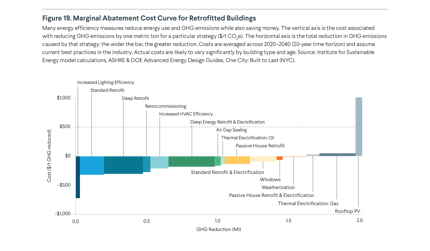

Figure 19 in the Carbon Free Boston report depicts the Marginal Abatement Cost Curve (MAC) for Retrofitted Buildings. The MAC highlights the essential role that efficiency plays in mitigating climate change while benefiting consumers. Many of the measures with a negative cost depicted – from increased lighting efficiency to weatherization – are addressed through Mass Save, our utility-administered energy efficiency program.

Environmental benefits resulting from Mass Save efficiency measures could be augmented by stronger appliance standards and building codes. Deeper efficiency via retrofits would be facilitated through Mass Save (which now includes incentives for heat pumps), but updated codes and standards would help to ensure the highest efficiency in the huge number of buildings expected to be built in Boston in the next decade.

Cities can green up the electricity supply for their residents and small businesses through Green Municipal Aggregation. However, there is also an opportunity and a need for cities to begin moving forward on greening up their municipal electricity loads. Municipalities can lead by example, demanding renewably generated electricity supply from regionally sited and newly commissioned projects (deemed "Class I" or "new" by Massachusetts and Rhode Islands statutes).

When municipalities drive demand for additional, new, in-region renewables, they help displace fossil fuels on our regional grid. In this way, cities and towns provide the impetus for more aggressive renewable energy requirements to be met by electricity suppliers. This, in turn, helps to pull the region more quickly toward grid decarbonization.

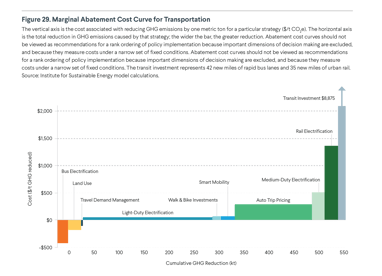

The CFB summary report includes a similar MAC for the transportation sector. Electrification of buses jumps out as the first strategy on a path to carbon neutrality. The report notes that 10% of Boston’s transportation emissions are generated by buses and the MAC shows that investing in electrification actually has a negative cost – meaning the benefits exceed cost. When we consider, also, the public health benefits, improved air quality, increased accessibility to clean transportation, etc., bus electrification is a no-brainer. Bus electrification is also something that cities can move forward on today.

The CFB summary report includes a similar MAC for the transportation sector. Electrification of buses jumps out as the first strategy on a path to carbon neutrality. The report notes that 10% of Boston’s transportation emissions are generated by buses and the MAC shows that investing in electrification actually has a negative cost – meaning the benefits exceed cost. When we consider, also, the public health benefits, improved air quality, increased accessibility to clean transportation, etc., bus electrification is a no-brainer. Bus electrification is also something that cities can move forward on today.

Reducing carbon emissions from transportation is not just about buses, though. Electric vehicles for those who lack transit options are also needed. Bills filed this session in Massachusetts and aimed at increasing the adoption of zero emission vehicles is one approach. National Grid's rate case docket, currently open before the Department of Public Utilities, is another. But in the more immediate term, increasing awareness about and access to charging infrastructure and EVs (as through our Drive Green program) is also key.

The modeling that has informed Carbon Free Boston underscores the reality that achieving carbon-neutrality by mid-century anywhere in our region is contingent upon states complying with their own GHG emission reduction and clean energy objectives. Additionally, the strategies identified in the CFB summary report are consistent with findings reported in the Massachusetts’ Comprehensive Energy Plan and the Commission on the Future of Transportation Report and Rhode Island's Transit Master Plan:

Consistency between CFB and these other studies – the result of comprehensive modeling that serves as the underpinning of strategy development and recommendations going forward – makes it hard to dispute what action should be taken and how those steps should be sequenced.

These studies introduce another measure of accountability for policy-makers. From this point forward, decisions makers considering next steps on climate action should be able to point to how proposed solutions cohere with what has been presented in each of these well-resourced, much-ballyhooed reports. This is as true for mayors and municipal leaders as it is for Governor Baker and his administration. Any reduction short of what the analysis says is imperative will not be good enough.

National Grid trucks line the street outside of Newport Fire Department Headquarters (Station One). Thousands of...

In his State of the Commonwealth address, Governor Baker committed Massachusetts to net zero carbon emissions by...

Comments